Victory for Allison Bailey

The barrister suffered direct discrimination and victimisation by Garden Court chambers on the basis of her gender-critical beliefs

I intended to return this week to the rise of “victimhood culture” and my theory that it is facilitating “toxic underlings”, but have (again) been derailed by events. The welcome distraction is Allison Bailey’s judgment in the employment tribunal, which was published on July 27th. I wrote about the hearing in two previous issues (about Kirrin Medcalf, Stonewall’s head of trans inclusion, in issue 6; Catherine McGahey, formerly of the Bar Standards Board, in issue 7).

Allison’s case was very complex, which was reflected in the length of the hearing (six weeks) and cost (£550,000, raised by crowdfunding). I listened to a fair bit of the evidence, and thought it pretty unlikely that she would win on the financial parts—not because I disbelieved her claim that the clerks victimised her by sending fewer clients her way after she expressed opposition to Stonewall and support for the LGB Alliance, but because a barrister’s earnings are, in the normal way of things, very variable. That made it hard to prove anything beyond doubt. I also feared that the connection between Stonewall and Garden Court, Allison’s chambers, was sufficiently loose that even if Garden Court was found to have discriminated against her by acting in ways Stonewall recommends, Stonewall would not be found liable.

Well, I was right on both counts, but the verdict still brought much that was cheering. Allison won on her central claim: that she suffered direct discrimination and victimisation by Garden Court on the basis of her gender-critical beliefs. For this she was awarded “aggravated damages”—which suggests the tribunal thought Garden Court’s behaviour was egregious.

And the hearing itself was immensely valuable, in that it forced adherents of the reality-denying bigotry that motivated the attacks on Allison onto the stand. It has now been said on oath by Stonewall’s head of trans inclusion that biological sex isn’t binary and that it changes through a person’s lifespan; that transwomen are not male and refusing to identify trans people as in every respect the sex they claim to be is transphobic and abusive; and that by raising concerns about predatory men using self-ID to enter women’s spaces, women are demonstrating their propensity to commit hate crimes against trans people, who will therefore not be safe anywhere near such women. Kirrin Medcalf claimed that these were not just her beliefs, but Stonewall’s institutional beliefs too.

And then Catherine McGahey of the Bar Standards Board defended the “cotton ceiling”, a repulsive analogy between lesbians’ knickers, seen as a barrier that keeps transwomen out, and the “glass ceiling” that stops women progressing in the corporate world. Amazingly, she compared trans-identified men attending a workshop to “strategize” ways to get past this barrier of prejudice—to sleep with women who don’t sleep with men, in other words—to the South African heroes of the anti-apartheid movement. Their techniques should not be assumed to be coercive, she said; rather, they were like the visionary actions of Nelson Mandela in seeking to unite post-apartheid South Africa in national pride behind the Springboks.

I’ve known for a few years now that these are the sorts of unpleasant beliefs that Stonewalls and its acolytes hold. But precisely because they are so unpleasant—and so fundamentally absurd—it’s hard to convince people that a famous, respected charity really does claim this sort of thing, and demand that anyone who disagrees is silenced. I think Allison’s greatest achievement was forcing these sorts of people to do their preaching under oath and skilful cross-examination.

Also welcome is that the judgment has given further substance to the category of protected gender-critical beliefs. In recent weeks the gender hardliners have been trying to spin the Forstater judgment as offering only barebones protection: only to mildly gender-critical statements, for example, or only if the company has neglected to write a sweeping policy on its employees’ social-media use. Maya is said by some to have been very careful in what she said while working at the Center for Global Development, but to have started spewing hate that would fail the test of being “worthy of respect in a democratic society” once she had lost her job.

These misrepresentations are intended to convince employers that they don’t really have to take account of those nasty women insisting on naming sex because the employment protections they have post-Forstater are so restricted that in practice most cases will fail. You can read some debunkings here and here, and an excellent long read by Peter Daly on the meaning of the Forstater judgment. (Daly is both Maya’s solicitor and Allison’s, but this was written before Allison’s verdict.)

Allison’s judgment is only first-instance, and therefore does not set precedent. Nonetheless, it has sway, and suggests the sort of reasoning that other tribunals are likely to employ in sufficiently similar circumstances. It is thus helpful in rebutting the silly claims that only the most mealy-mouthed expression of gender-critical beliefs will be protected, since Allison spoke far more trenchantly than Maya. Moreover—and this is entirely new—her beliefs about Stonewall itself were judged to be protected.

Both before and during the weeks of the hearing, Allison said again and again, in many different ways, that Stonewall’s position on trans issues was misogynistic and homophobic (specifically lesbophobic), and that the organisation actively sought to roll back women’s rights, and to destroy lesbians’ ability to define themselves and set sexual boundaries that exclude all men, however they identify. Now people can feel safer in arguing that their employer should stay the hell away from Stonewall and other consultants with similar agendas. As long as it’s properly worded, a note to HR arguing that a company should not join any scheme like Stonewall’s Workplace Equality Scheme, or if it is already a member, should leave, is likely to be a “protected act” (something it would be unlawful for your employer to sanction you for).

Incredibly, both Garden Court and Stonewall tried to spin the verdict as a win. The usual suspects popped up to try to help. “Allison Bailey took on Stonewall, and she lost against Stonewall. Everything else is noise,” tweeted Owen Jones, perhaps Britain’s most unpleasant journalist. “Delighted to see that Alison Bailey - founder of the sinister ‘LGB Alliance’ has lost her legal case against #LGBT champions @stonewalluk,” tweeted SNP MP John Nicolson, perhaps Britain’s most unpleasant politician.

Garden Court’s press statement was so dishonest that I think it deserves an award. Indeed, I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s stealth-edited at some point, so I’ve archived it. It entirely omits the fact that it lost on Allison’s main claim and was found guilty of discrimination and harassment, with the claimant awarded aggravated damages. If you didn’t already know that, you would be genuinely puzzled to reach the end and read that it was considering an appeal.

Meanwhile Stonewall and that rainbow Pravda, Pink News, went big on the fact that Stonewall wasn’t found guilty of anything. Again, this was a very partial truth, at best. Stonewall’s stance wasn’t vindicated; what the employment tribunal ruled was that its connection with Garden Court was so loose that the legal bar of “instructing, causing or influencing” was not reached.

One of the ways in which Garden Court was found to have victimised Allison was by acting on a complaint about her from Stonewall. But the tribunal decided that Garden Court could have decided not to pay any attention to that complaint—and indeed, it ignored some other requests from Stonewall without suffering consequences. In other words, Allison’s employer did the dirty work of victimising and discriminating against Allison off its own bat, even though Stonewall egged it on.

That is a very low standard by which to judge an expensive consulting charity that purports to make employers more welcoming and inclusive for sexual minorities. “Pay us, we’ll give you unlawful and bigoted advice which, if you follow it, could see you losing on a discrimination case in the employment tribunal—but you’ll be liable, not us.” I’ve seen more compelling sales pitches.

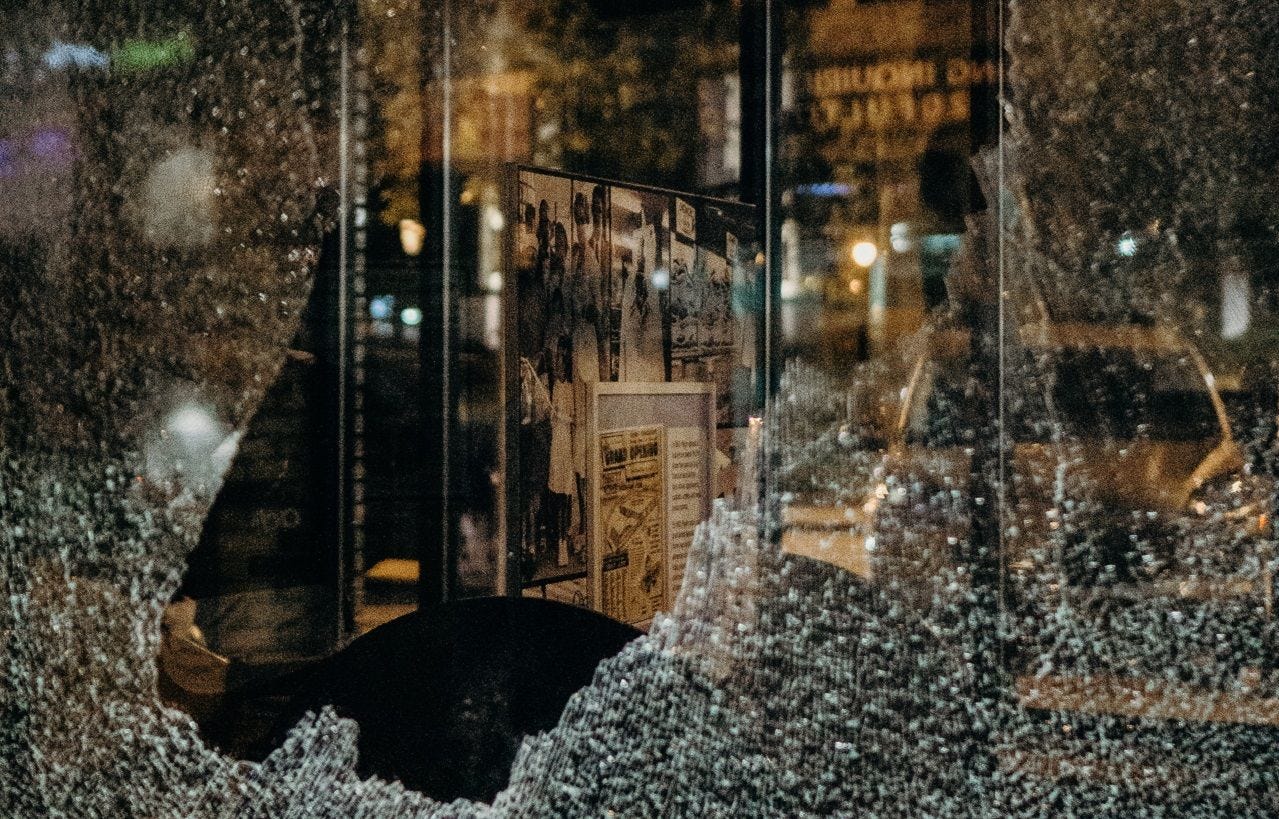

Here’s an analogy to help bring home the point. Suppose you, a private individual, pay someone with a good reputation to advise you on what to do this evening. “Go out and smash shop windows,” that person says. You decide that sounds like a fine idea, go out and smash some shop windows—and are arrested and charged with criminal damage.

How likely are the police or courts to go after the person you paid to advise you to commit your crimes? I think there would have to be evidence that they had actually incited the crime, perhaps by offering an inducement for obeying them, or credible threats of punishment if you if you did not. If you could take their advice or leave it with no consequences, the crime is probably entirely on you.

My reading of Allison’s judgment is that Garden Court and Stonewall are in roughly this position. (To be clear, Garden Court was not found guilty of criminal behaviour, but of unlawful discrimination and victimisation.) Stonewall advised Garden Court to break equality and employment law, and to discriminate and victimise. On the most plausible reading of a letter from Kirrin Medcalf to the head of chambers, Stonewall says Garden Court should end all association with Allison. But the contacts between Garden Court and Stonewall were relatively limited, the tribunal found, and there was no obvious means whereby Stonewall could either reward Garden Court for following its advice or punish it for failing to do so.

It should surely be clear by now that anyone with “fiduciary duty”—a legal obligation to act in another person’s or organisation’s best interests—should be writing an urgent memo advising ending all ties with Stonewall, or any of the dozens of other charities and consultancies that peddle similarly unlawful and bigoted advice. They should also be advising that employer check all staff policies and practices that may already have been influenced by such advice. People with fiduciary duty include a company’s general counsel and members of its risk committee and board. They all have a legal responsibility to give advice that does not cause financial harm, and to do their best to ensure that the organisation complies with relevant regulations and laws.

After all, Garden Court may not have behaved unlawfully towards Allison Bailey because Stonewall told it to. But Stonewall did tell Garden Court to act in a manner that has now been found unlawful, and moreover, that is how it advises every company, school, university and so on to act. It is surely cold comfort to a head of HR, a member of the risk committee, a CEO or general counsel that if they behave as Stonewall recommends, they risk losing at an employment tribunal—but they, not Stonewall, will carry the can.