Glorifying mutilation

How mastectomy became the symbol of “trans liberation”

I’ve been thinking about something pretty grim on and off the past month or two: the way mastectomy is now openly celebrated as a matter of diversity, identity and pride. There are children’s books with illustrations showing mastectomy scars on “boys”, and breastless women have been photographed topless for the covers of magazines that wouldn’t normally put topless women on their covers. But it all ramped up in June (the Holy Month of Pride), and though we’ve clearly been softened up for this for quite some time, now I’m seeing it everywhere.

This post was first published about a year ago, but for some reason it is the sole post that proved impossible to port over to Substack when I moved my newsletter. So I’ve had to create a new post and republish. Sadly, it’s as topical now as when I wrote it.

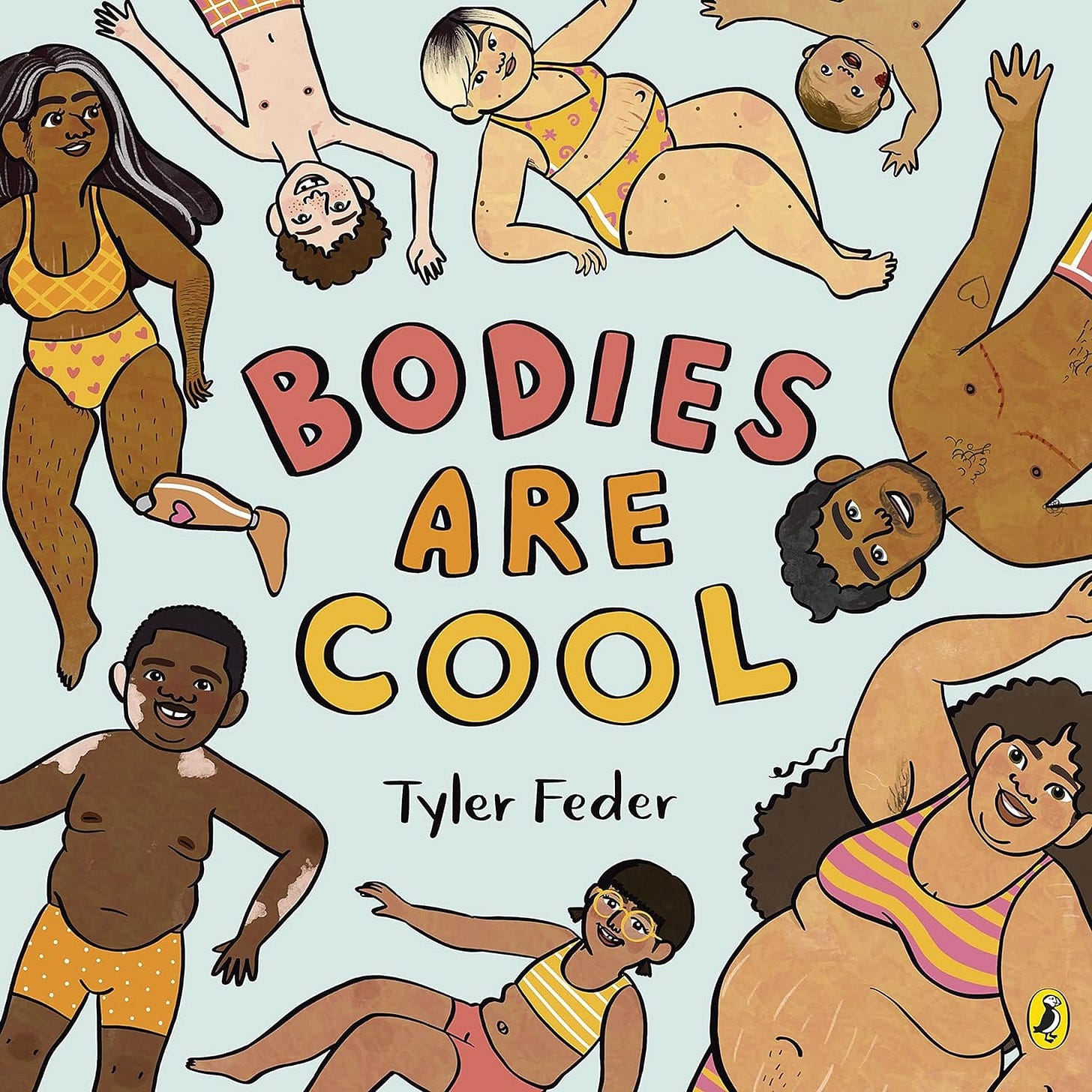

To pick just two examples of the softening up, here’s “Bodies are cool”, a book for 1-5 year olds published in 2021. It features people of varying sizes and skin colours, with various disabilities — and on the cover, a hairy-faced “man” with mastectomy scars. It’s hard to see this as anything other than a cue for parents and nursery staff to indoctrinate children too young to have established sex permanence in the wrong-body narrative.

And here are two pictures from magazine covers in the past two years, both featuring topless women. One, for Glamour magazine, shows a pregnant, breastless woman with men’s clothing painted on her naked torso; the other, for New York Magazine, is a woman in Y-fronts with a ridiculous bulging neophallus, and the scarring on her thigh, where the flesh was taken from — and of course the obligatory mastectomy scars.

It’s depressing to think that women’s natural bodies would be too obscene for magazine covers, but that once mutilated they’re perfectly fine. My point isn’t that decency laws are different for men and women — men’s and women’s bodies are different, after all — is that a woman’s breastless, post-surgery chest is being treated as if it’s the same as a man’s chest, which never had breasts in the first place. I can’t think of a clearer illustration of the way that sexual objectification is located in women’s bodies and not men’s, and not in men’s gaze either, but in the woman’s actual flesh and blood. It’s the same mentality as insisting that women should cover up to avoid inciting men’s lust.

What made me think about all this more recently were two particularly shocking examples.

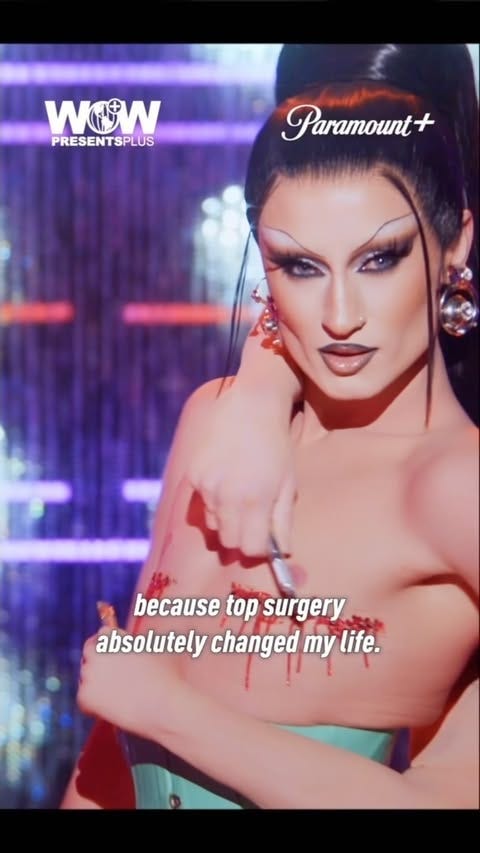

The first was Kate Gottlieb, aka Gottmik, a transman who performs drag — the mind-exploding end-point of thinking identities are real and bodies aren’t: a woman who pretends to be a man pretending to be a woman. She appeared on RuPaul’s Drag Race in 2019, pre-mastectomy. Just a year previously, RuPaul had said he didn’t think a “bioqueen” — a woman who dresses up in the same parodic fashion as drag queens — would have any place in the show. Needless to say the trans lobby turned on him, and he swiftly apologised.

Recently, Gottlieb was back on a spinoff show, RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars. She performed topless, with her mastectomy scars emphasised by two glittering red crescents made of Swarovski crystals. In a see-through plastic surgical-waste bag she carries what look like the bleeding breasts. Here’s a short video of the performance, if you can stomach it.

It’s the strangest thing to see how mainstream it is to defend this obscenity. Here’s Entertainment Weekly claiming that the only criticism comes from “Conservatives” and “far-right conspiracy theorists”. Here’s Digital Spy rounding up prominent people to praise the look — Ariana Grande and Paris Hilton, as well as various drag queens I’ve never heard of.

Here’s Advocate, a prominent LGBT news outlet, giving Gottlieb the space to peddle the “transition or die” narrative: “It’s not self-mutilation at all like everyone online is trying to push. It’s truly gender-affirming surgery that changed my life. I would not be here today without that surgery, honestly.” And here’s an interview with her in Them, an online LGBT magazine. “I want it to be intense and in your face,” she says, “but at the same time, I want people to look at it and be like ‘Wow, that’s so pretty.’ The crystals were a good way for me to make it beautiful because top surgery is a really beautiful experience.”

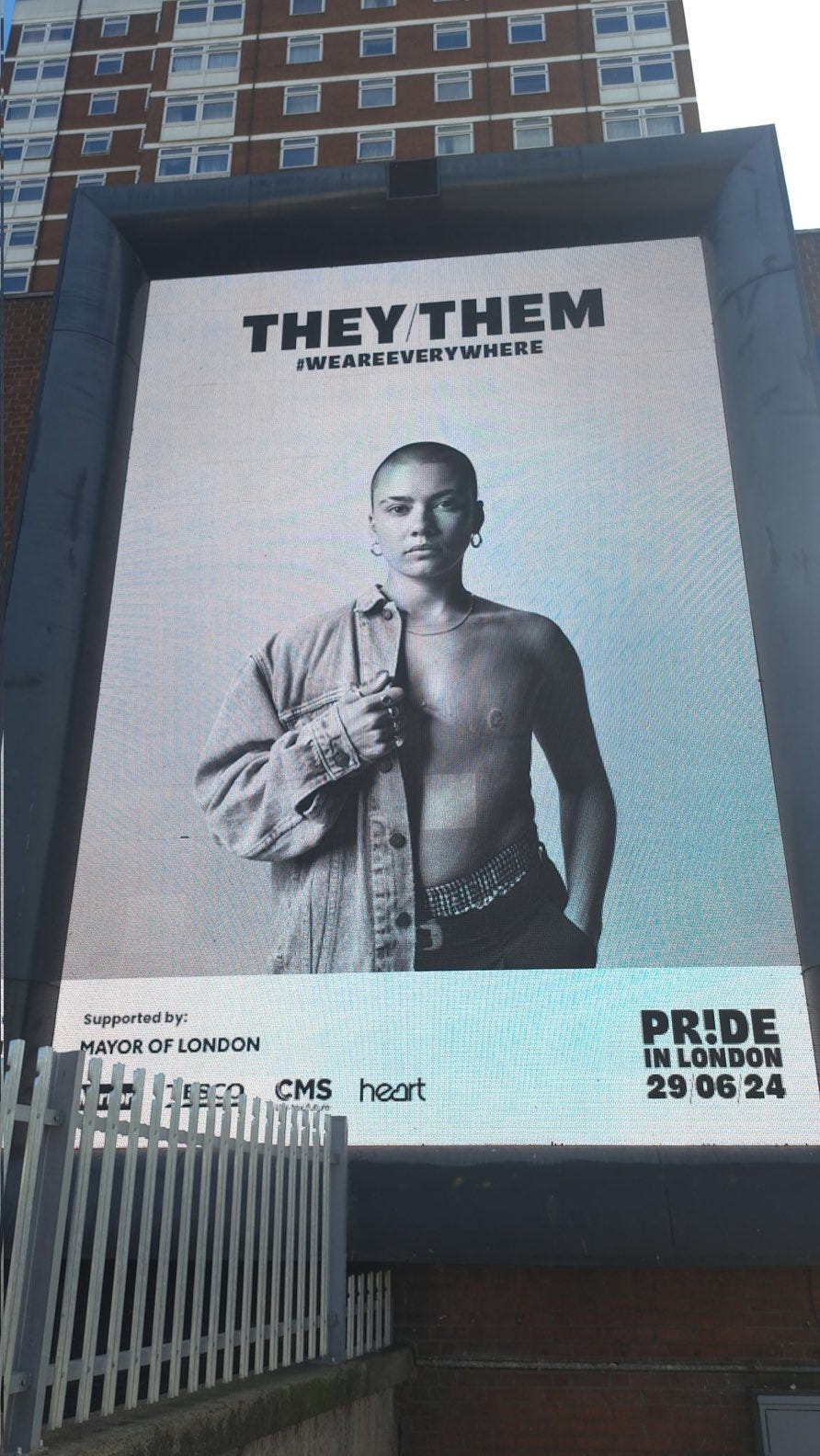

The second moment that shocked me was a billboard displayed in London as part of Pride Month celebrations. It’s very different from Gottlieb’s explicitly pornified drag-queen look. Instead of camping up and glamorising the gore, it makes the scars nearly invisible.

This is in a public place and unavoidable – on a roundabout near Shepherd’s Bush tube station. I don’t know that little children would look at it and ask their parents uncomfortable questions. But I do know that for a teenage girl who dislikes the hair-and-nail extensions, false eyelashes and pumped-up lips look that have been foisted on her generation, it’s probably aspirational. Here’s Joan Smith in UnHerd on how the Mayor of London describes himself as a “proud feminist” and yet supports this rampant misogyny.

All the ways in which trans ideology encourages people to hate their bodies and mutilate themselves are bad. But the other ways aren’t celebrated in this pornified, aestheticised and public way. Rather, they’re minimised with phrases like “gender-affirming care” and “nullification”, or sanitised with medical terminology (“penile preservation vaginoplasty”). There are no photos in public places of bottom surgery. (Although, since we apparently now live in hell, maybe that’s coming? Maybe it’s already there on PornHub??)

As others, notably Victoria Smith (aka @glosswitch) have written, when cutting off your breasts is an acceptable way to deal with discomfort with having breasts, or with the reaction of others to your breasts, then women who don’t cut theirs off can be deemed to have “identified into” those consequences, which include being leered at, groped and objectified. What I want to discuss here is something else: the invitation to dysphoria that this normalisation offers, and the alacrity with which young women will hear that invitation.

Humans have always modified their bodies, in ways from the minimal (henna tattoos, plucked and painted eyebrows, false nails) to the drastic (neck stretching, lip plates, bound feet, lip filler). When I was a child most older women had got rid of their eyebrows almost entirely by a lifetime of plucking; it was usual to paint a thin semi-circle far above their original position. Now many young women paint on thick black shapes that resemble broken isosceles triangles, usually accompanied by enormous false eyelashes. If you get used to doing this, your natural face will seem exceedingly odd to you.

Body modifications often involve features that are physically and culturally expressive – eyes, mouths, hands, genitals. It’s not just women’s bodies, or even just women’s sexual characteristics, that are modified. Horrifying things are done to teenage boys’ penises in certain tribal traditions – I’m too squeamish to describe or even link to any description.

The part of the face that many people end up fixated on is their nose. I think it’s in part because it sticks out and so you don’t see it in profile when you look in the mirror. That means you don’t get used to it in the way you get used to your ears. But it’s also because noses are culturally significant. Think of Michael Jackson shaving his own away, piece by piece, as parts of his attempt to excise his blackness.

When you start to think about a bit of your body this way, you can quite quickly become extremely miserable. If that misery becomes a fixation that interferes with ordinary life it’s known as body dysmorphic disorder. Sufferers may seek out surgery – but this rarely helps, and the obsession may continue with the same body part (think of Michael Jackson’s nose) or move on to another.

I think breasts are a particularly, perhaps uniquely, appealing target for body dysmorphia – and not only because they are the most pornified body part in our culture (in Brazil, where I worked as a foreign correspondent from 2010 to 2013, it was all about the butt). Breasts are an inherently strange body part, for a start, very large for something that has no bones or muscles to give them structure. They can be very painful in the run-up to menstruation. You have to strap them down to run. At the end of the day, unfastening your bra can be a big relief — but not wearing one isn’t comfortable either, if you have to move around.

Even more strange is that the function of breasts is solely for others, not their owner. In our pornified society we jump immediately to thinking about the male gaze, but I mean something much older than that: their evolved functions. which are to feed babies and to signal reproductive status. Before they develop a girl is unlikely to be able to get pregnant. They change shape and consistency if a woman has ever been pregnant, and more so if she’s ever breastfed. Their lack of any inbuilt support means that, absent bras, they function as a pretty reliable indicator of ageing.

While I lived in Brazil I visited the Amazon region several times to write about the state of the rainforest. On one trip I visited an aldeia (literally a village, but Brazilians use the word for an indigenous settlement) where the chieftain had been a small child when the tribe made “first contact” with the modern world (typically, such tribal groups are aware that there are very different people in some wider world, but have at most glimpsed such people at a distance). He was younger than me, I think around 40 at the time.

He was a remarkable person who spoke Portuguese and travelled around the country advocating for what Brazilians call índios – indigenous tribal peoples. I also met his mother, who was already an adult before first contact. She didn’t speak Portuguese and found me very strange – my skin colour, my eye colour, my hair. She, like all the other women in the aldeia, was topless. In such a setting, it’s impossible to ignore the very obvious signal of ageing and record of reproductive history provided by a woman’s breasts.

Towards the end of my stint in Brazil I interviewed a Brazilian photographer in his swish modern apartment in São Paulo about a project he had recently finished visiting indigenous peoples in various countries to document their attitudes towards modern medicine. I had been asked to write a paragraph or so to accompany each of a series of photos from his time with a Brazilian tribe. The piece seems to have been lost from The Economist’s online archives. But I vividly remember the interview, at which his assistant, a beautiful young woman, was also present. She told me that upon meeting anyone in the tribe, what they wanted to know about her was her reproductive status. They would — without asking — lift her top to look at and feel her breasts to judge whether she had ever been pregnant and whether she had breastfed. (She hadn’t, which made her in their eyes a complete anomaly.)

So girls whose discomfort at their bodies settles on their breasts aren’t doing something surprising or odd. They aren’t even doing anything that requires us to live in a pornified culture where breasts are fetishised (though we do). They’re raging against the body part that expresses, more than any other, what’s difficult and uncomfortable about female embodiment.

We don’t live in a society of a couple of hundred people, every one of whom knows who’s related to whom and how, who’s with whom, who’s been pregnant, who’s miscarried, who’s fertile and who isn’t. We don’t think of ourselves as primarily part of a group and only secondarily as individuals, and we don’t expect to know about other people’s “private lives” – a pretty moot concept in an aldeia. We think of ourselves as individuals. That makes breasts inherently problematic, because they are troublesome for us and useful for others — to see, to touch, to be nourished by, to know things about us. They are the body part that says: men may be able to pretend to be islands, but women can’t.

The trans movement has therefore landed on precisely the most dangerously appealing body part in its mutilation cult. Cutting off your breasts is an assertion of individual, independent personhood, in a culture that glorifies individuality and independence.

Without breasts you’ll be able to go topless when other women aren’t allowed to, and exercise without wearing a sports bra. Any child you might have in the future can be fed equally well by anyone. Of everything a woman can do, breastfeeding is about the most incompatible with independence and self-determination.

That you might regret mastectomy when you’re older is, unfortunately, a big plus. I’m reading a very interesting book at the moment, dating from 2000, “Cool Rules: Anatomy of an Attitude”. It’s impossible to sum up — I’ll definitely have to read it several times. But one of its many astute observations is doing things that older people say you’ll regret is definitely cool.

You’re unlikely to yet have the life experience that would make you cautious about elective surgery. Anyone older than about 35 will know that you don’t mess with bodies without expecting consequences. By then they, or people they love, are likely to have had operations, to have experienced imperfect healing and post-operative infections. They’ll know how much recovery hurts and how long it takes, and how scar tissue is never quite the same. Young people are easy prey for the idea that humans are like Mr and Mrs Potato Head, able to swap body parts out and in.

All this makes it really hard to say anything useful to a teenage girl or young woman who’s decided she wants to cut off her breasts. The reasons why she shouldn’t do it are the same as the reasons she wants to, and the life experiences that might make her think again are probably in her future. Her breasts don’t have any function for her, except to signal to others — and she presumably has actively taken against the main signal relevant to her age group, namely to look attractive to men. I really wouldn’t fancy trying to explain to a her that nobody is solely an individual either. That we are only people because there are other people, and that we only have identities because others identify us. That’s precisely the problem she is in flight from.

More and more it seems to me that behind the trans movement, despite its constant insistence that everyone is unique, is a deep desire to see humans as basically interchangeable. There’s nothing special about being a mother, nothing special about this interpersonal bond over that one. “Found families” — friendship groups — are as meaningful as the ties of blood. I think this sounds like hell; to these girls it’s precisely what they want.

I’m actually at a loss to think about how to counter the commercialised trans movement’s glorification of mastectomy. I know quite a few women have complained to the Advertising Standards Regulator about the London Pride billboard, on the grounds that it is offensive, glorifies self-harm and breaks the rules on advertising cosmetic surgery. Let’s see if they get anywhere: if the ASA turns a blind eye it’ll be part of a pattern in which regulators and quasi-regulators treat anything to do with trans issues as an exception to the rules they’re meant to enforce.

I think the only hope is expensive medical malpractice settlements. Many doctors, especially in America, seem happy enough to cut girls’ breasts off in order to help them achieve their short-term “embodiment goals”, without any serious medical justification. Large payouts and soaring insurance premiums would put their patients’ long-term interests back into the equation. Otherwise, I very much fear that mastectomy will become completely normalised.

Thank you a hundred times over for this article. It needs screamed from the rooftops!

I had a double mastectomy 10 years ago because of breast cancer. I was 36. I hate it being minimised as ‘top surgery’. It’s major surgery which leaves you with a variety of problems from scar tissue to reduced mobility.

It is not a simple or straightforward option for gender dysphoria and it makes my blood boil when I hear it being described as life saving for trans people.

I had to wait 2 months for my surgery on the NHS and that was with a cancer diagnosis. Needless to say, I do not think this should ever be available for trans people on the NHS and certainly never for children.

I have even witnessed doctors telling women that if they changed their mind they could just get implants in the future. Giving the completely wrong impression of what this surgery does.

I’ve actually been speaking to a lovely girl in America who has de transitioned and is wondering about whether to have a reconstruction. Utterly heartbreaking.

Great article, very informative. However I do disagree on one point, which is that breastfeeding for me has been one of the most empowering, grown up, affirming and independence making as an adult woman experience that I have ever had. I’ve spent 5 years doing it with 3 babies and it’s on my list of top ten all time pleasures, even though it hurts like hell to start with. I think we need to teach young women about the privilege of nourishing new life and the joy that goes with that. It puts having periods into a gloriously different perspective.