Joyce Activated, Issue 2

I feel I owe it to my new subscribers to talk a bit about The Lunch. If you haven’t read the pieces by Julie Bindel and Suzanne Moore, you definitely should—and also the op-ed by Janice Turner in which she compares the outrage about middle-aged women meeting to eat, drink, laugh and discuss our rights with the opposition to the Suffragettes.

Rosie Jones, a comedian I had never heard of before, said the pictures of The Lunch provoked her to have a “mad, angry cry” (do flick through #MadAngryCry on Twitter, it’s surely Jones’s funniest work). Craig Murray, a former UK ambassador whose chequered history I have been reading about, open-mouthed (here’s a gem-studded piece from 2008—read right till the last sentence), took major exception to us women owning mobile phones. Women started sharing pictures of themselves Lunching While Female Without Permission From Men. Transwoman India Willoughby and others engaged in full-blown body-shaming, as documented in the Critic by Jean Hatchet.

I love annoying misogynists (both male and female) by simply existing. And I think that forcing believers in gender-identity ideology to speak is the most effective way to defeat them. For example, the animating idea behind Willoughby’s body-shaming tweets is that women who don’t “woman” properly aren’t even women. It’s hard to imagine anything more regressive, and the more often Willoughby and others are given the opportunity to make clear what they believe, the more opposition they will provoke and the sooner the day will come when everyone agrees that how you look and behave doesn’t change your sex.

At various points during The Lunch, women stood up to say a few impromptu words. They were variations on a theme: how much strength we had drawn, individually and collectively, from the willingness of one world-famous person to risk her reputation and future income to stand with us, and with everyone else under attack for supporting women’s rights and opposing the medicalisation of gender non-conforming children. More than one woman said Rowling had been part of what kept them going through the darkest moments of their lives. There were some tears.

I haven’t been monstered like many of the other women in the room, and I didn’t cry. But there have been many times since I first steeled myself to say what I really thought about the mad idea that men can be women that I have needed to cheer myself up. Although I laughed at #MadAngryCry and rolled my eyes at Murray and Willoughby, this stuff is depressing and crazymaking. I didn’t know the word “gaslighting” three years ago; now I do.

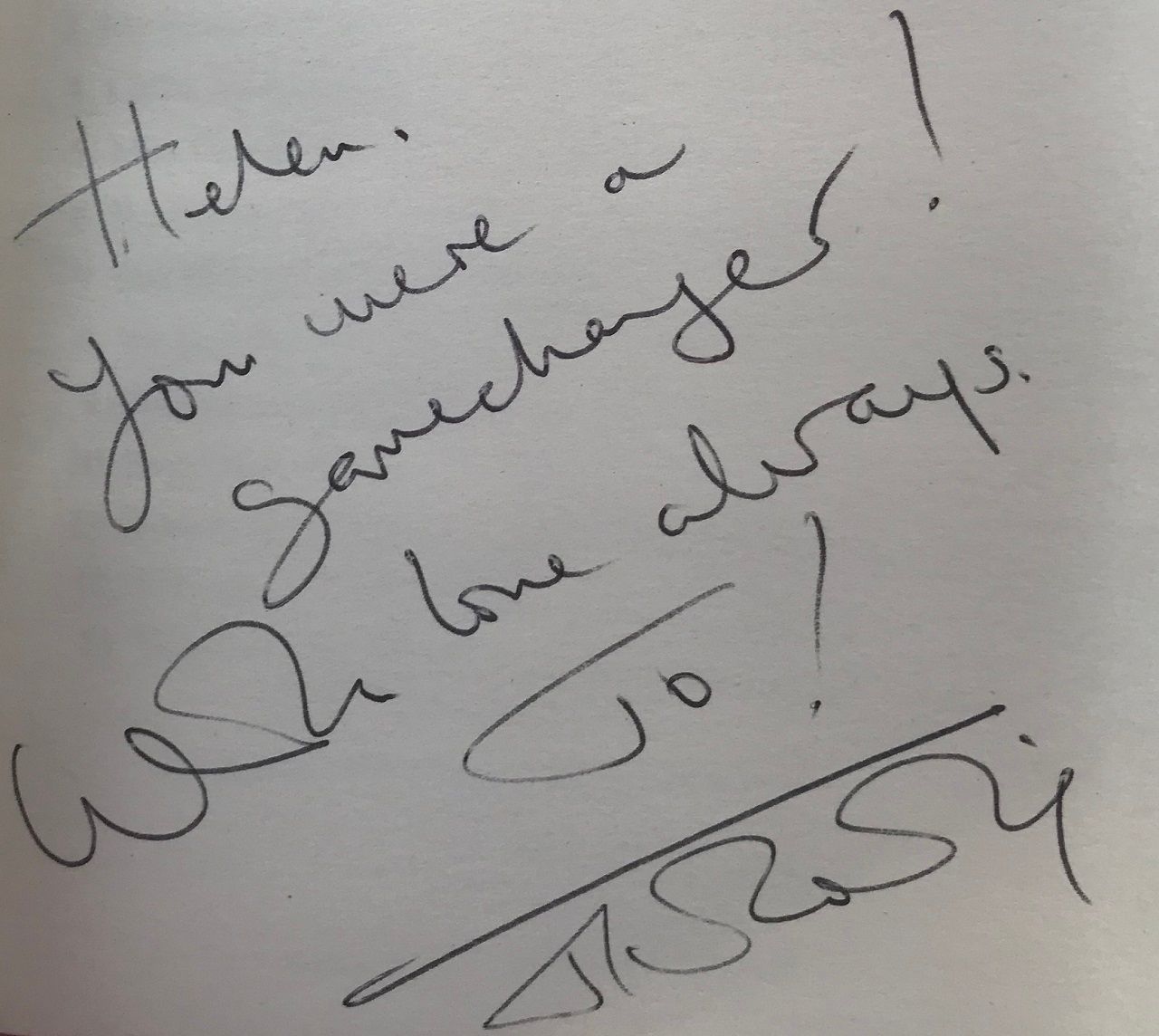

To cope, you need support and a community. For me, both have largely come through the new connections I have made by speaking out. But it hasn’t done any harm to have the occasional DM from Rowling. At The Lunch, I asked her to write in the front of a pre-publication copy of the paperback edition of my own book (due out May 5th; in the next few weeks I’ll arrange getting signed copies to those of you who have subscribed to this newsletter for a year, thank you!). I’ll treasure it always.

I hope that she too took comfort from our gratitude and solidarity, and that it helps sustain her under a torrent of abuse that sometimes seems never-ending. If you missed the beautiful piece by Nick Cohen in the Critic, when Rowling first started to speak out in 2020, you should read it now. He explains why she has become the global hate figure for gender transubstantiationists: not despite her generosity and compassion, but because of them. “She lives by the standards she sets in her work,” he writes. “She doesn’t take the ‘easy route’, which is why the travelling circus of actors, trolls and celebrities for whom the easy route is the only route cannot abide her.”

It’s easy to imagine that if you were rich like Rowling, you would say whatever you pleased, because you wouldn’t have to fear losing the means to make a living. In fact, cowards and conformists seem to be overrepresented among rich people. I think the reason is that if they say anything that goes against the current consensus, they are putting a larger future income stream at risk. I’ve noticed that people whose income is independent of their words—in particular, the youngish retired—are way overrepresented among those who oppose gender-identity ideology under their own name.

Which brings me to the latest row about transwomen—men who identify as women—in women’s sport. It’s obviously a travesty, and yet hardly anyone in the entire sporting ecosystem says so. Athletes who are still competing fear being dropped by their teams or sponsors if they cause controversy. Coaches are even more expendable. Retired athletes, by and large, are still trying to make money from sponsorship, coaching or commentating. It’s pointless to say that people should tell the truth when doing so would blow up their entire life. And so increasing the amount of honest speech means changing the incentives.

A quick recap (for detail, read Chapter 9 of “Trans”). In 2003, sport’s highest authorities, the International Olympic Committee and International Amateur Athletic Federation, decided that post-surgical male transsexuals (men who had undergone castration and genital remodelling) could compete as women. Since such surgeries were rarely performed, and almost always on people well past their physical prime, the new rule had little impact—I don’t know of any transwoman who competed in elite female events in the decade following. But in 2015 the IOC decided that men could skip the surgery and qualify for women’s competitions by taking drugs to suppress their testosterone. Nearly all sporting authorities followed the IOC’s lead.

The result has been a series of individual controversies. Last year Laurel (Gavin) Hubbard, an out-of-shape, 43-year-old male New Zealander, made it to the Tokyo Olympics as a “female” weightlifter. Earlier this year Lia (William) Thomas, a 23-year-old male student at Penn State University, smashed women’s times in university swimming events. And in the past few weeks Welsh cyclist Emily (Zach) Bridges, a 21-year-old who set men’s junior records at the age of 18, was lined up to compete in major women’s events. Only at the last minute did the UCI, cycling’s governing body, rule that Bridges was not yet eligible to compete as a woman on a technicality: namely that his registration as a male athlete had not yet expired.

The coverage was fascinating. I was particularly struck by an interview in the Times by Matt Dickinson, its chief sports writer, with Pippa York (Robert Millar), a retired competitive cyclist and transwoman who received a ban for doping back in 2004. York transitioned at age 40, and is now high up in the administration of British Cycling, a member of its diversity and inclusion advisory group. (Another member is Robbie de Santos, communications director of Stonewall.) Last year the group was charged with reviewing BC’s “transgender and non-binary participation policy”, which allowed male athletes to declare themselves female for the purposes of competition provided they lowered their testosterone levels. It concluded that the policy was fine.

“It felt important to talk to York before writing about [Lia] Thomas,” wrote Dickinson. Why exactly, he did not explain: the question of whether males should be allowed into supposedly female-only sports is surely not a matter for male people at all. Granting female athletes anonymity to share their honest opinions might have made more sense. (British women cyclists were reportedly readying themselves to boycott races if BC hadn’t backed down, and a recent survey by the Cyclistes Professionnels Associés, an international body that represents professional cyclists, found that more than 90% of female cyclists opposed males being allowed to identify their way into women’s competitions.)

The interview is a remarkable illustration of how men who identify as women sometimes thereby gain licence to talk like sexist pigs. York speaks dismissively of Thomas’s teammates, who complained about having to share not only the pool with a man, but their changing room, too: “A piece about Lia Thomas walking around with genitalia out. You just know it didn’t happen.”

This is a perfect example of why using “preferred pronouns”—that is, referring to someone of one sex using the pronouns of the other because that is what they want—can be so harmful and deceptive. What we have here is one man sneering to another about women who have been forced to accept a third in a space where nakedness is the norm—in other words, to accept what would in any other circumstances be recognised as voyeurism and indecent exposure. To call York and Thomas “she” would wilfully obscure what is being described, and by whom.

So much for the male athletes whose dearest wish is to be female: why does everyone else play along? One reason, I think, is that many regard the consequences as trivial. Most people who care about sports don’t care about women’s sports. The same journalists who airily dismiss the problems caused by allowing male athletes to identify as women by saying that there are very few of them, and they’d be miserable otherwise, do not use similar arguments about unfairness that affects men—doping, say, or fancy shoes or swimsuits, or whether amputees who run on blades have have an unfair advantage over able-bodied athletes.

But mostly, it again comes down to incentives. In my book I say that the inclusion of male athletes “presents female athletes with what economists call a collective-action problem. The classic example is the ‘tragedy of the commons’, whereby jointly owned land becomes infertile because everyone entitled to graze their animals on it has an incentive to take more than their fair share. All female athletes will lose from admitting males into women’s sports, but each individually has incentives to stay quiet. Trans athletes are, after all, not numerous, so each woman can cross her fingers and hope to get through her career without coming up against one. Athletes’ professional lives are short, so even a year or two distracted by a fight that may not be of personal benefit is a huge sacrifice. And sponsors do not like controversy, even in a noble cause.”

I think the sponsors are the key to changing these dynamics. The reason is the precise nature of their incentives: not the glory of victory, or making a living, but burnishing their reputation. This makes them particularly risk-averse and skittish—but also prone to turning on a dime. In brief, if a controversial stance ceases to be so, sponsors’ opinions can change dramatically and decisively.

Consider the evolving response to “taking a knee” as a protest against police brutality. At first teams and sponsors were unenthusiastic: in a country as polarised as America, the safest brand ambassador is apolitical. By 2017 big brands associated with the NFL were making statements supporting athletes’ rights to speak, but trying to distance themselves from what those athletes said, all the same. Colin Kaepernick, who had started it, was out of a job. In 2018 Nike decided to lean in, choosing Kaepernick as the face of its new advertising campaign. It was a risky decision, but turned out well. And then, after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, attitudes flipped. Now any sponsor, team or politician who dares suggest athletes should not take a knee receives pushback—even in countries where police almost never murder people.

At the moment, sponsors clearly think that an athlete speaking out for fairness in women’s sports—and therefore the exclusion of all males—would be a liability. Some are even willing to make their donations contingent on organisers admitting males and forcing women staying quiet about it.

Last week a case in point hit the headlines. Peter Stanton, a safety engineer who is the main sponsor of a major cycling event, theWomen’s CiCLE classic in Melton, Leicestershire, withdrew funding of £15,000 in protest against British Cycling’s decision to exclude Bridges after the UCI ruling. “Whilst fully supportive of women’s sport, I also have many friends and colleagues within the transgender community whom I feel that I would be letting down if I did not make a stand to show my support for their rights,” Stanton said.

When the news broke, two groups that campaign for fairness in women’s sport, Fair Play For Women and Sex Matters (for anyone who doesn’t know, I’m now Director of Advocacy for Sex Matters), stepped in with replacement funding. The race promoter gratefully accepted the offer as a guarantee that would ensure the event went ahead, but is now crowdfunding and seeking a longer-term replacement sponsor.

I doubt Stanton, who uses “they/them” pronouns, minds being shown up as someone who doesn’t care about fairness in women’s sport. But other sponsors probably would. I’m guessing that some will be pondering what they would do in a similar situation—not because they have an unbendable commitment to fair play, but because it is dawning on them that one day soon they may be faced with the choice between sticking with a women’s event that has decided to exclude males in order to deliver fair competition, or destroying the event. The job for women’s-rights campaigners is to leave them in no doubt that the second would look worse.

To receive future issues, subscribe to Joyce Activated.