What we could have been doing instead

A lament for the time we’re having to waste on this fight, and for the destruction of social, emotional, economic and intellectual capital

A short post this week, and one with a frivolous hook that quickly turns serious.

If you are not a subscriber to my weekly newsletter, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

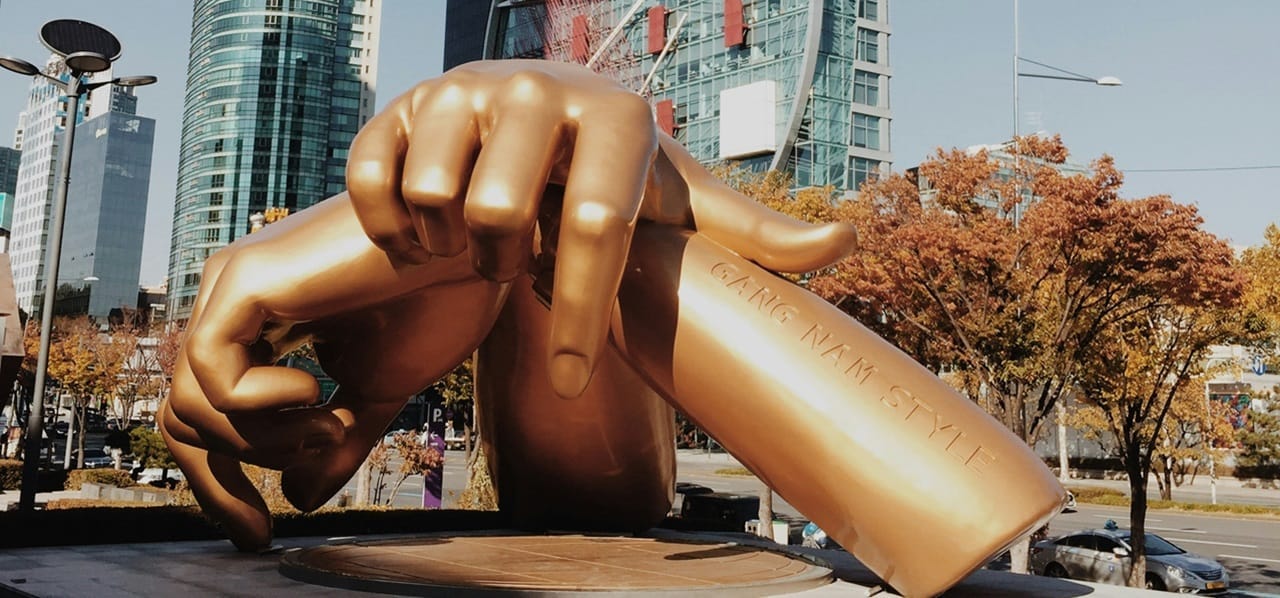

Almost a decade ago, the year after I returned from being a foreign correspondent in Brazil to work at The Economist’s head office in London, my colleagues in the data and graphics teams had a great idea for a daily chart. The video of “Gangnam Style” on YouTube had just passed 2 billion views, making it the most-watched video ever and breaking YouTube’s counter. (Innocent times; it’s passed 5 billion views now, and “Baby Shark Dance” by Pinkfong recently passed 14 billion – and typing that makes me feel very old, since until I searched just now I had no idea what or who Pinkfong was, let alone what “Baby Shark Dance” might be. And now I wish I hadn’t searched.)

My colleagues did a quick sum and calculated that 2 billion views equated to more than 16,000 person-years watching PSY pretend to gallop on the spot all around Seoul. So they made a chart comparing this to other notable achievements of humanity, and titled it “The hidden cost of Gangnam Style: What humanity could achieve if it weren’t galloping in front of computer screens”.

Gangnam Style breaks YouTube's counter: here's what humanity could have done instead: http://t.co/OJNvevpRob pic.twitter.com/6FNhmp7Hfs

— The Economist Data Team (@ECONdailycharts) December 4, 2014

In the past five years, as I’ve devoted my time to finding different ways to say “there are two and only two sexes, people’s sex can’t change and that matters, especially for women”, and to pointing out the disastrous consequences of pretending otherwise, I’ve been haunted by that phrase. What could those of us devoted to this fight have done instead?

It’s not like the world is so perfect that we have time to waste arguing things that literally everyone knows. Even just restricting ourselves to the long-standing causes of women’s-rights campaigners, there is so much to do: between two and three women are still killed every week in the UK by men, and there is still a great deal of physical and sexual violence perpetrated by men against women. And of course there are other causes too.

And “Gangnam Style” isn’t actively destructive. Watching it is at worst a few minutes wasted, and if you don’t watch it, nothing happens. The problem for us is actually bigger: it’s that we’re spending our time on this fight because if we don’t, other things are wasted, in particular the social, emotional, economic and intellectual capital tied up in the institutions that are being hollowed out from within. I’m not even sure some of them can be saved, at this point: Stonewall, for example, is now exclusively a force for evil. I’d be interested to hear from American readers whether the ACLU, HRC and GLAAD are similarly lost causes.

I’m particularly sad about the destruction wrought in the women’s sector. The charities that help women who have experienced male violence, whether physical or sexual, have always existed on a shoestring and stagger from one short-term grant or contract to another. They often fold. And now they have to cope with the whole gender bullshit on top, and it’s causing chaos. Good people are leaving, and bad people are being enabled. Our recent report from Sex Matters details the sad state of affairs.

I think British universities are still rescuable – although the next decade or so is crucial; if mandatory “diversity statements” – in effect “loyalty oaths” – now common in some American states, notably California, take off here then quite quickly there will be nobody in universities outside the ultra-progressive bubble, and no academic freedom left to protect. I’m very dubious about the potential for rescuing some other institutions, notably the BBC – but we have no choice but to try because of its special status as the taxpayer-funded national broadcaster.

I’m less worried about commercial media outlets, for two reasons. One is that they have a long history of reinventing themselves and coming back from misjudgments, often when the editor changes. Another is that they are subject to market forces, and setting up a new media brand and gaining reach has never been easier.

If there’s a common viewpoint that nobody mainstream is representing, someone pretty rapidly comes to fill it – whether that’s Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan, Megyn Kelly, The Public, Persuasion or Gript Media. These can be a very big deal: Joe Rogan’s multi-year deal with Spotify was reportedly for $250 million and Gript, a newish Irish outlet with just ten staff, some of them part-time, recently got an exclusive interview with Elon Musk.

Britain has two new television channels, GB News and Talk TV, which fill an anti-Woke, pro-Brexit, anti-immigration hole – this combination of political positions is pretty common among the general public but utterly unrepresented by any of the mainstream television broadcasters (it isn’t mine, in case anyone thinks it is). Their viewership isn’t high, and broadcast costs are far higher than for a podcast or subscription newsletter, but still, they’re there. And then there’s radio, which is far cheaper. Talk-show hosts like Julia Hartley Brewer give space to people mainstream broadcasters ignore (like me), and reach many people.

I worry about the resulting epistemic bubbles. But I’d worry more if there were no alternatives. I find my home country, Ireland, an interesting case study on this. Gript is anti-EU and was initially funded in part by the anti-abortion Life Institute, with which it shares an address. Again, not my political position! But without Gript, it’s no exaggeration to say that Dublin’s incestuous bubble of self-satisfied politicians and NGOs would face barely any scrutiny.

When I was writing my book, Gript was where I found information about Barbie Kardashian (which I later verified privately with a court reporter for a mainstream paper who hadn’t been able to get any stories about Kardashian published). One of its reporters, Ben Scallan, is the only person I’ve seen ask ministers probing questions live about planned hate-speech laws, gender self-ID or the level of immigration. Reporters for mainstream outlets all worry too much about continuing to be able to move the right circles to probe the sore points that politicians would much prefer to avoid.

When it comes to the media, I trust the process of creative destruction described by Joseph Schumpeter. There’s no reason to think the New York Times or any other paper will, or even should, last forever, or that it would be disastrous if it failed and something else took its place. Schumpeter’s point wasn’t merely that the failure of market leaders is natural, it was that it’s often part of a process that makes the entire sector more productive and stronger. Newcomers are better at innovating than incumbents because they’re not burdened with legacy technology or processes, and they’re not emotionally or intellectually committed to methods or viewpoints that are becoming obsolete.

I wonder if it’s the same with organisations like Stonewall and GLAAD? Maybe I shouldn’t grieve for their loss; maybe it’s just part of the circle of life (and now I feel old again – I just checked, and “The Lion King” turns 30 this year…). And maybe it’s the same with universities? Hardly anything as old as Oxford or Cambridge, or even Harvard or Princeton, is still around, after all. Maybe it’s fine that they fail, and something else replaces them.

I think this is probably right for the campaigning charities that reached the end of their natural lives (in the case of Stonewall – if the ACLU had stuck to civil liberties instead of pivoting to social justice there would still be plenty for it to do). Yes, they have great brand names that they are still coasting on, and it will take some time more before those are comprehensively trashed. And yes, they have their hooks into lots of big businesses – but big business is an unsentimental beast, and as soon as association with a once-great charity stops serving its interests, they’ll drop it without a second thought.

With universities I’m more concerned, because higher education is not just about what the students learn; it’s a signalling device. A large part of the value of a degree from a well-known institution comes from being admitted in the first place: it’s nothing to do with what you learnt when you were there. That gives incumbents an enormous advantage and makes it hard to break in, especially in professions where jobs are hard to come by. It takes something truly egregious to destroy that kind of brand value. I’m not even sure the toxic remarks by the presidents of Harvard, UPenn and MIT late last year will do it.

If you are signed up for free updates or were forwarded this edition of Joyce Activated, and you would like to subscribe, click below.

So we have two types of problems, and both are more serious than the time we shouldn’t have to spend. The first is that good things that don’t deserve to die – women’s centres, for example – are being destroyed, and there isn’t even any creation to balance it out. The second is that institutions that have reached the end of their natural lives, like Stonewall – and arguably at least some universities – are staggering on. If we want to see something better, we need to become zombie-hunters.