When all the help isn’t helping

How mass mental-health interventions in schools may be helping to cause the crisis in youth mental health, rather than to cure it

My topic this week was suggested by a paper evaluating a programme intended for universal delivery to teenagers via schools. Based on “dialectical behaviour therapy” – a version of cognitive behaviour therapy intended for people experiencing unpleasant emotions very intensely – its intention was to help children learn to manage difficult feelings. But the outcome was a bust. As the tweet that brought the paper to my intention summarised it:

Giving free therapy to a bunch of teens who don't have mood disorders caused a bunch of them to develop mood disorders, and caused their relationships with their parents to get durably worse. https://t.co/hUKihvxz2l

— Lyman Stone 石來民 🦬🦬🦬 (@lymanstoneky) October 6, 2023

The replies to my tweet suggested that the idea that therapy can harm rather than help struck a chord. One was from a self-described “anxious over-thinker”, who said that the last thing people like her needed was encouragement to ruminate. What helps, she has learned, is to turn her focus outwards and keep busy. Another woman said that watching her daughter at university made her conclude that young people nowadays are pretty much expected to be mentally unwell, to such an extent that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Some offered school-related observations. One woman said her child’s school had built a “peace garden” to “honour” a child who had taken their own life, which she thought hugely counterproductive: “a space for sad teenagers to think about suicide and death and loss and being sad”. A man said his girlfriend’s 13-year-old daughter had been told in school to rate herself on a scale of 1 to 10, according to how often she had thought about self-harm. “She was completely freaked out by it.”

This reminded me of a relative who told me that her 11-year-old daughter’s class had been encouraged to download and use a mental-health app the school had paid a significant amount for. When she answered the questions it asked, it told gave her a “well-being score” of 75%. “Her face dropped,” said her mother: this girl is a sweet-natured, clever, popular child whose usual mood could scarcely be better – unless a silly app tells her that actually, there’s considerable room for improvement.

If someone’s lucky enough not to have a mood disorder, the best thing for a school to do, it seems to me, is nothing. And if someone does have such a disorder, getting them to ruminate freely on their mood seems deeply unwise. Depression is a condition of disordered thinking: a person can’t be depressed without thinking sad thoughts, which are often about themselves and their situation. Encouraging them to think about themselves and their situation is therefore risky, and should be done only under the guidance of someone properly trained, who can encourage better thinking patterns at the same time.

It seems so obvious that interventions created for people with difficulties and intended to be administered by experts are unlikely to be effective when offered to everyone by non-specialists who may, at best, have attended a one-day course. And indeed, researchers are confirming the uselessness, even harmfulness, of efforts to raise awareness of mental-health issues at a population level.

So why does nearly every parent I talk to have a similar story, whether about a school or university? Why have things gone so wrong with the way we think about young people’s mental health?

One reason, I think, is fear. Young people really do seem to be suffering a mental-health crisis, with soaring numbers self-reporting, and being diagnosed with, mood disorders such as anxiety and depression, and with ailments such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). It’s not feasible to offer them all specialist help: there aren’t enough therapists, and therapy is expensive. That makes cheap-and-cheerful mass interventions using mobile apps or school staff look appealing.

The thinking seems to be that these are, at least, better than nothing. That improving everyone’s mental health a little bit will have something like the impact of reducing salt in processed foods on the number of heart attacks.

I think this is badly mistaken, in part because mental distress isn’t like heart attacks. If you increase awareness of the causes and symptoms of heart attacks, you will decrease the number of people who die of them. More people will avoid the things that raise their likelihood of having one, and more victims will recognise the symptoms earlier, while they can still be saved.

Increasing awareness of mental-health problems, by contrast, can make people less mentally well. This seemed obvious to me, but since it clearly isn’t obvious to all the people encouraging children to rate their mood, think about friends who’ve killed themselves and self-diagnose conditions like ADHD online, I did a bit of searching to back my intuition up. And I found this paper, which posits that interventions intended to increase awareness of mental-health problems may lead people to interpret milder distress in this way, and to report it as such.

The result isn’t merely to lower the cut-off point for what counts as a diagnosable mental-health condition – it actually makes people more miserable. “Labelling distress as a mental health problem”, the authors say, “can affect an individual’s self-concept and behaviour in a way that is ultimately self-fulfilling”. If this is right, at least part of the recent rise in mental distress is “iatrogenic” – caused by treatment. It’s as if we were increasing the amount of salt in processed foods while thinking we were reducing it.

Another consequence of increasing awareness of mental-health issues is the rise of “therapy-speak”: words and phrases such as “triggered” and “defence mechanism” that have made their way out of textbooks and consulting-rooms into general use. If these are useful in communicating, great – new, more precise words can help people articulate their experiences in productive ways. I certainly see a lot of narcissistic rage and gaslighting in transactivism – neither of them terms I knew until relatively recently.

But they can also disguise the fact that someone doesn’t really know what they’re talking about, or used less to understand problems as a first step towards solving them and more as an alternative to doing so. Friends a bit younger than me tell me it’s become very common for children to tell their classmates that they’re “having a bad OCD day” or that “my ADHD is out of control today, so leave me alone”. These conditions are often self-diagnosed, and become self-fulfilling prophecies in that they’re taken as licence for consequence-free bad behaviour of the sort the children associate with those diagnoses.

One therapist I know told me that when she started in practice about a decade ago, specialising in teenage girls, she was astounded at how insightful all her clients were. At first she thought she was just really lucky; later she realised they were repeating flippant nostrums they had learned online. This made it harder, not easier, for her to help them, since they were (unintentionally) masking their lack of insight into their mental state.

How are we not noticing that things being done to children in schools to make them mentally healthier are quite probably making them worse? I think it’s in part a bias towards action – action of any kind. I call this the “politician’s fallacy”: something must be done; this is something; therefore this must be done.

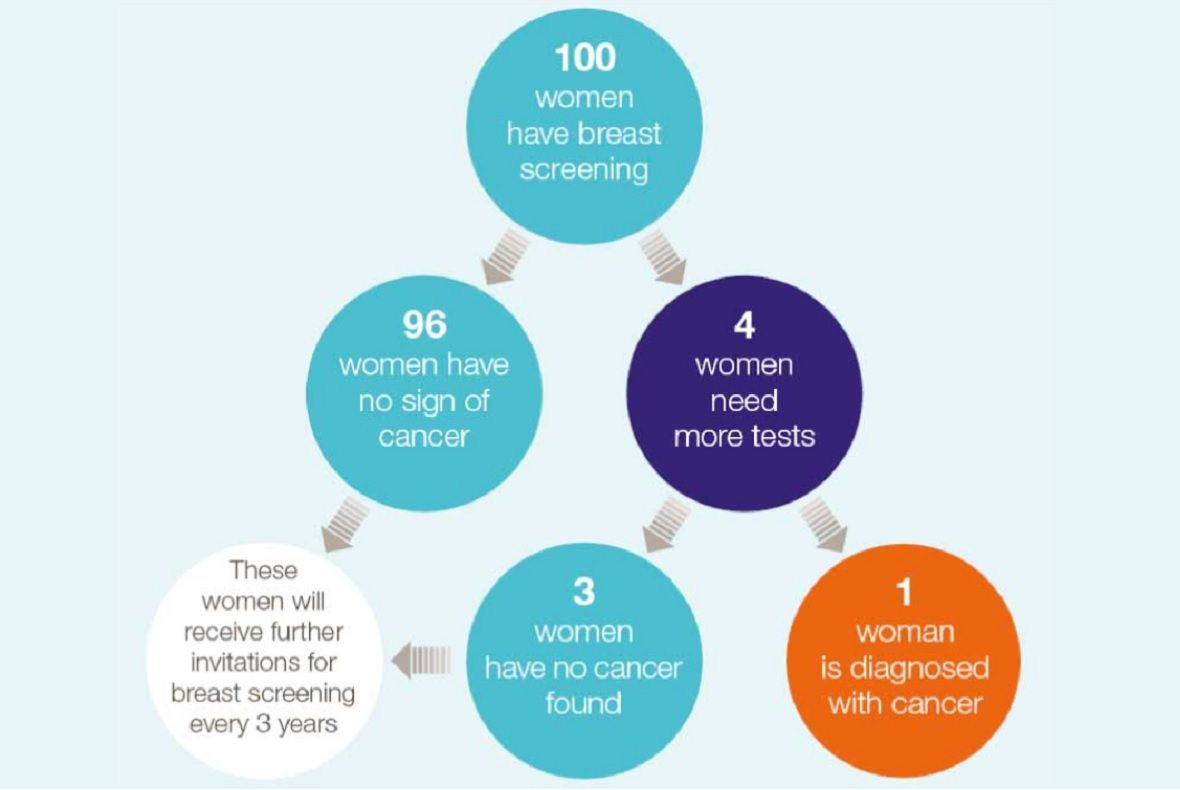

It’s reminiscent of the way screening programmes can, unless carefully calibrated, do more harm than good. If you don’t already know this, take a look at this excellent page about population screening for breast cancer via mammogram produced by the NHS, which does the world’s best cost-benefit analyses of such mass interventions. It has calculated that starting at 50 and offering scans every three years until age 71 gives the best outcomes: the best balance between lives saved by spotting cancers that would otherwise have proved fatal, and women needlessly scared by false positives or harmed by treatment of cancers that would not have killed them. (The trade-offs work differently if you have a family history of breast cancer, in which case you may well be offered earlier and more frequent screening.)

This chart explains why you shouldn’t panic if you have an abnormal mammogram: three in four are false alarms. The article also explains that even among the women who do have cancer, most of those cancers would not have become invasive and would not have needed treatment.

Personally, I trust the NHS’s medical statisticians to have done the cost-benefit analyses and come up with the optimum approach. But if you live outside the UK, you may well be doing far more than the optimum amount of medical testing. When I lived in Brazil I was offered mammograms yearly by my doctor, and I refused on the grounds that if I had still been in the UK I wouldn’t have been (I was there from age 42 to 45, and have no family history of breast cancer).

My Brazilian doctor was supportive, and told me he wished he was able to persuade other women of this reasoning. But the mentality for people with private health insurance was “the more testing the better”. It seems so counterintuitive that you might be better off not knowing if you have cancer – people don’t realise how many cancers never become invasive. Similarly, when it comes to mental health, the best advice can be to leave well enough alone.