The case of Allison Bailey

Bailey alleges that her chambers, Garden Court, together with Stonewall, victimised her for her gender-critical beliefs, her lesbianism and her backing for the LGBA

For the past two weeks I have been part of a group of people co-operating to take detailed notes on the online hearing of Allison Bailey’s case in the employment tribunal (hence the lateness of this week’s issue, for which apologies—it’s time-consuming work). Bailey alleges that her chambers, Garden Court, together with the LGBTQ+ charity Stonewall, victimised her in various ways for her gender-critical beliefs, her lesbianism and her backing for the LGB Alliance, a new charity that focuses on advocacy for lesbian, gay and bisexual people only, as Stonewall used to do.

The outcome is of course enormously important for Bailey, an impressive woman who has transcended a great deal of personal trouble to become a criminal-defence barrister. (For more details about her case and life history, read her witness statement.) But the reason we are putting so much effort into capturing what is said in the hearing itself (recording it is a criminal offence) is that this is an unparalleled opportunity to hear adherents to the gender dogma say, under oath and cross-examination, what they profess and insist that the rest of us must, too.

In this article I’ll focus on the testimony of Kirrin Medcalf, Stonewall’s head of trans inclusion. Medcalf is a transman who formerly identified as non-binary (she submitted written evidence to a parliamentary select committee in 2020 under the title Mx Medcalf). I’m going to use female pronouns for her, though male ones were used in the hearing, not just on principle, but because when someone is an out-and-out sex-denialist, as Medcalf is, I think it’s relevant and important to be clear what sex they are.

Medcalf’s testimony has already sparked a fair bit of media interest, in part because of how it was conducted. (Medcalf is actually 24, not 34, as the linked article says.) As her cross-examination by Ben Cooper QC, Bailey’s barrister, was about to start, Ijeoma Omambala QC, representing Stonewall, nonchalantly informed the judge that Medcalf had a “support person” in the room. What sort of support, asked Cooper? “Emotional support,” came the reply.

Cooper protested that no request for such an adjustment had been made. The judge decided to permit it all the same, provided the person could be seen on camera. That, said Omambala, would require the room to be rearranged to get “all of them” in shot—to which judge, Cooper and perhaps others chorused: “All of them?”

To cut a long story short, it turned out that in the room with Medcalf were the “emotional support person” (an unnamed friend), a “technical support person” (later revealed to be a trainee in the solicitors’ firm Stonewall uses), Medcalf’s mother and a dog. We never saw the friend, who presumably hadn’t signed up to be on camera and skedaddled when that turned out to be part of the deal. And so Medcalf gave evidence with a solicitor finding pages for her in the evidence bundle, her mother sitting in the background and her dog at her feet—but no “emotional support”.

All in all, it was a brazen bit of courtroom drama. But the meat of the day was Cooper’s cross-examination of Medcalf. In representing his client, he had licence to ask whatever supported her case and he was also insulated from the sort of shaming that normally stops people asking pointed questions of gender ideologues. Medcalf, for her part, was under oath and bound to answer. She could not deflect those questions with the usual cries of “transphobia” and “no debate”.

As Cooper rifled through emails and meeting minutes to point to places where Medcalf or colleagues had called gender-critical feminists TERFs, described perfectly reasonable statements of fact as “transphobic” and so on, he left no opportunity for Medcalf to indulge in what I think of as the “no one says” style of argument—as in, “no one says sex and gender identity are the same” or “no one says that trans people actually change sex”. Of course they do—how else are we to interpret demands that men who identify as women be treated as women in sports, prisons and everywhere else that people are separated by sex? But trans ideologues have had remarkable success with the strategy of insisting that “we’re talking about gender, not sex” when challenged, only to return to demanding that self-declared gender identity be treated as sex once their critics have given up and gone away.

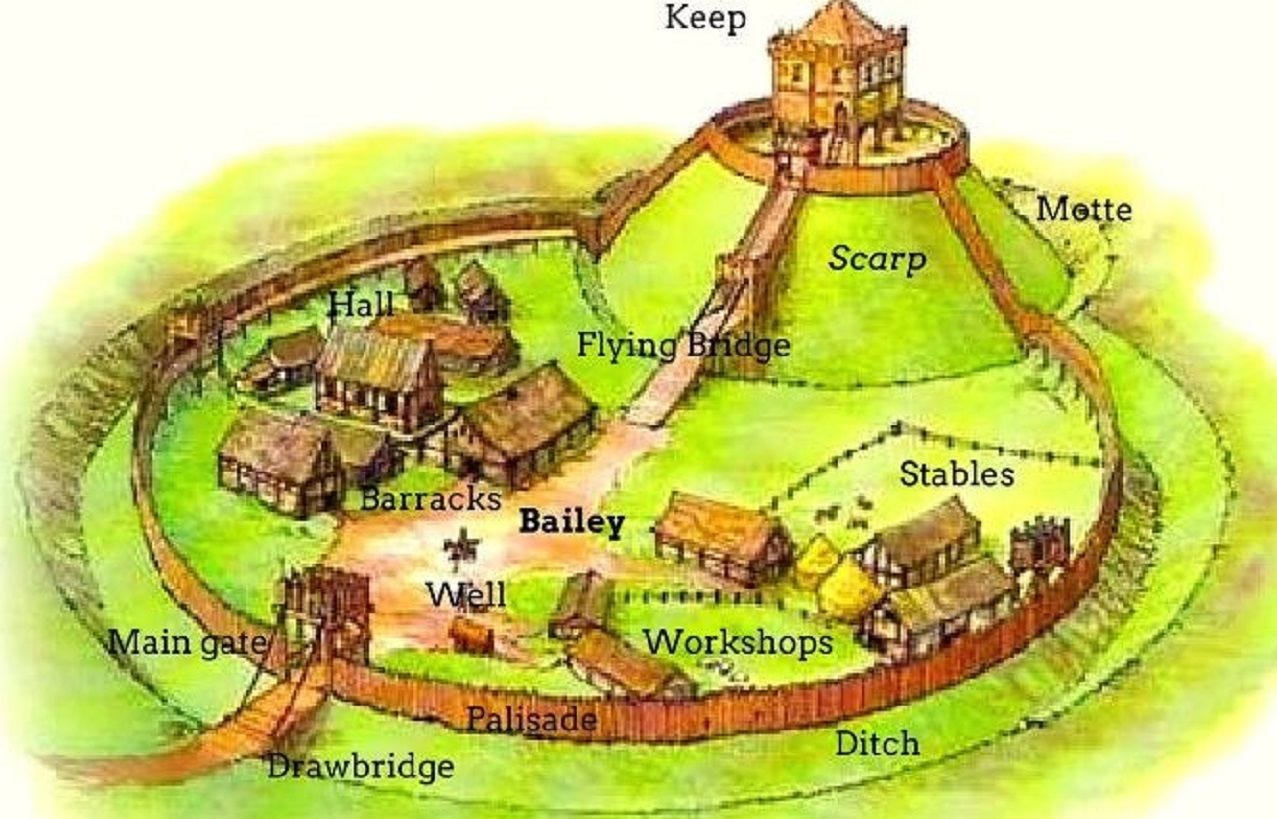

This is an example of the “motte and bailey” technique, which is named by analogy with the way some mediaeval fortifications were designed. The bailey was a large area that was only lightly defended, perhaps by nothing more than a ditch. The motte was a fortified tower to which the bailey’s residents could retreat when they came under attack, only to re-emerge when the threat was over. The analogy is with a style of discourse in which you make maximalist claims when no one is paying attention, switch to superficially similar but more defensible claims if challenged, and return to the original position when critics have given up and moved on.

Sex Matters has published the highlights from Medcalf’s testimony, and they’re worth reading in full. Here, I’m going to focus on just a couple of points. One is the toxic mixture of fragility, entitlement and narcissism it displayed, which is typical of much transactivist discourse. The other is the conclusive evidence it provides that transactivists really do deny the material reality of sex.

For evidence of Medcalf’s fragility, you need only look at the cast of support people (and dog). For her sense of entitlement, consider that in her early 20s, just five weeks into a new job at a famous charity, she sent an email to the heads of a barristers’ chambers demanding that it take harsh, decisive action against a woman whose qualifications, experience and life history should have inspired her utmost respect. And she felt entitled to do that simply because that woman had tweeted in forthright terms about the conflict between the rights of women and same-sex attracted people, and the demands of transactivists.

Here’s an extract from Medcalf’s email:

“…for Garden Court Chambers to continue associating with a barrister who is actively campaigning for a reduction in trans rights and equality, while also specifically targeting members of our staff with transphobic abuse on a public platform, puts us in a difficult position with yourselves: the safety of our staff and community will always be Stonewalls [sic] first priority. I trust that you will do what is right and stand in solidarity with trans people.”

The most obvious reading of these words, as Cooper put to Medcalf, is that unless Garden Court kicked Bailey out, Stonewall would turn against the chambers, with unspecified consequences. Medcalf insisted that what she had intended to convey was rather her fears about the safety of any trans-identified person who might attend a meeting held at Garden Court of the Trans Organisations Network, a collection of lobby groups that Stonewall had convened to advise it on trans issues. She claimed to have interpreted Bailey’s tweets about the reality of sex, and the problems caused by denying it, as a clear precursor to violence: “I have seen people who say exactly all of this stuff and then gone out and done the most horrific hate crimes.”

Bailey’s very concerns about the risks posed to women when men who identify as women are allowed into women’s spaces were, according to Medcalf, merely further evidence that Bailey herself might resort to or incite violence. “When people are scared they want to defend themselves,” she told the tribunal. “Whether that’s physically or just shouting: ‘there’s a man in the women’s toilets, get him out’ and then someone grabbing one of my colleagues and manhandling them. Anything like that could have happened. It demonstrated a picture of someone very active and committed in their beliefs and it feeds into their actions and that is enough to make me really concerned about myself and my colleagues entering any space, especially a confined space such as a toilet, where Ms Bailey might be.”

This is a classic example of a technique called DARVO, which stands for “deny, attack, reverse victim and offender”. It is employed by narcissistic abusers to undermine their victims, and shift responsibility for the harm they do onto those victims. To be clear, I’m not accusing Medcalf herself of being a narcissist, or abusive—I don’t know her, I’m not a mental-health professional and nothing she said suggested she had the slightest proclivity for violence. I’m saying that the line of argument she presented—one she expressly attributed to Stonewall—is one that denies reality and casts victims as oppressors, and that this is indicative of a narcissistic worldview.

Bailey is a middle-aged woman. How likely is she to be able to rough up a male person, however he identifies? How likely is she even to take the risk of challenging one who has already shown his lack of concern for women’s boundaries by entering a supposedly female-only space? It is not “trans people” who are at risk when people use facilities intended for the opposite sex: it is women—whether they are trans-identified women who are foolhardily entering men’s spaces, or trans-identified men who are entering women’s spaces. But if you deny the reality of sex, you lose the words and conceptual categories to see this.

Sex-denialism ran through Medcalf’s entire evidence, and was openly stated in several places. Bailey has paid a high price in stress, notoriety and money (she crowdfunded £550,000 for legal fees) in order to force Stonewall to put its beliefs and their consequences on the record. The least I can do is help to amplify what was said.

One instance came in discussion about a meeting in which Stonewall employees and others discussed the (ultimately successful) feminist grassroots campaign to force the Office for National Statistics to alter its guidance on the census “sex question”. Initially, the ONS had said that everyone could answer according to the sex they identified as—even though a separate, voluntary question asked about gender identity. After a lightning judicial review forced the ONS to backtrack, it changed its guidance to say that people had to answer according to what it said on their birth certificate.

That campaign, according to Medcalf, was motivated by bigotry and bigotry alone. Asked by Cooper whether it is inherently transphobic to deny that a trans person is literally the sex with which they identify, she replied: “Yes, to…seek to erase their existence on government records is an act of transphobia.” She claimed that “previously, trans people were able to answer in any way they wanted to reflect their lived reality. And what was being done here was to remove that and only putting gender assigned at birth, or sex assigned at birth, however you want to use that word.”

Cooper then asked a series of questions about which beliefs constituted or were evidence of transphobia. He started with “the gender-critical view that someone’s sex is a biological thing, a characteristic that is not changed or affected by gender identity”. That might be motivated by transphobia, Medcalf replied, though wasn’t necessarily. It was however “incorrect”, because “biological sex is made up of a multitude of characteristics that change over a person’s life cycle.”

Next Cooper asked Medcalf about the view that “transwomen should not be given access to certain single-sex spaces: toilets, changing rooms, rape-crisis centres”. Definitely transphobic, she replied, adding that “I take issue with the words ‘allowing access’. It’s about removing access, removing a certain section of women from services because they are trans.”

What about “misgendering”, or referring to people by the pronouns for their sex, as I am doing here for Medcalf? Transphobic. In all circumstances? “Yes, unless that trans person as an individual has asked you to do so, to refer to them as men for their own safety.” (I think what Medcalf is trying to say is that a person who wants to conceal their trans identity might ask others to refer to them according to their sex in order to avoid being “outed”, and that going along with that would be non-transphobic misgendering.) What about describing any particular transwoman as male, excepting such situations? Transphobic, said Medcalf, “and I’d add abusive to that as well.” In each case, Medcalf said that these were not her personal positions alone, but Stonewall’s institutional positions too.

What of the phrase “adult human female”—was that inherently transphobic, Cooper asked. “It’s used within transphobic circles,” Medcalf replied. A woman describing herself that way is “identifying themselves as holding transphobic beliefs and willing to inflict hate crimes on others”.

Cooper then tried to get her to see that people might oppose gender self-identification for non-transphobic reasons—to no avail. He started with: “One of the concerns that gender-critical feminists like the claimant have is that if you make it difficult to say to a male-bodied person: ‘Sorry, you can’t come in to this space’; if you make that the norm, then bad men—not transwomen but bad men—will seek to exploit that, because bad men do go to extraordinary lengths to abuse women. That’s not a transphobic reason, is it?”

According to Medcalf, it is not only transphobic, but bigoted in several other ways, too, “because policing the actions of women because of the potential actions of a man is inherently sexist and misogynistic. And if it’s directed at a specific minority of women, like transwomen—or it could be any other minority of women—then it is prejudiced. In the same way that eight years ago we had this thing of saying that the burka should be banned because a man could disguise himself in a burka and access women’s spaces. That does not mean we should be policing how Muslim women should be using these spaces, and the same is true for transwomen. ‘Transwomen should be excluded from women’s space because of the potential for a man to abuse’—women should never be policed based on what men do.”

Cooper then put to Medcalf that when she said “transwoman” she meant “any person born male who identifies as a woman”. But that didn’t pass muster either. “What I mean is any woman who has a trans history,” she replied. “I wouldn’t say that transwomen were born male; they’re born as transwomen. And part of that journey is being perceived as male.” So Cooper rephrased, putting to Medcalf that the group she identified as “transwomen” included “people with male bodies”. Medcalf objected to that too. “Transwomen have transwomen’s bodies,” she said. “They don’t have male bodies. I have my own body; it’s for me. It doesn’t belong to any man or any woman.”

I doubt Medcalf had any idea just how crazy all this sounds to most people. As a consequence of spending years refusing to defend or even discuss their ideas, transactivists live in an unusually impermeable “epistemic bubble”—a knowledge-making and knowledge-sharing community that includes only voices that agree with each other.

Until recently, I thought the two big problems with epistemic bubbles were that people within them wrongly thought everyone agreed with them, and that they were ignorant of the reasons why others didn’t. I now see a third, far larger, problem. If an epistemic bubble forms around an idea that has no connection whatsoever with material reality, and with everyone else’s claims and beliefs about reality—that sex is not real, say—then the discourse within the bubble can mutate without hindrance. The whole community can float off into the stratosphere and there’s no telling where it will end up.

And here for an article I wrote for the Daily Express, on the sex-denialist nonsense that activist groups are pumping into schools.