Invasion of the science snatchers

What happens when “truthiness” meets “trust the experts”

In 2005 American television comedian Stephen Colbert coined the word “truthiness” for statements that “feel right” but for which there is no evidence. These range from ignorant repetition of falsehoods or misremembered facts to deliberate propaganda. Colbert did several segments around the time—and an entire turn at the annual White House correspondents’ dinner in 2006—about George W. Bush’s alleged fondness for the genre. The word came back into fashion in discussions of Donald Trump, though as many commentators noted, what Trump says often doesn’t even feel like truth, and his fans don’t believe it, but like him saying it all the same.

What is the defining characteristic of truthiness that sets it apart from propaganda or falsehood in general? I’m not massively convinced by what Colbert himself said—roughly, that truthiness consists of convenient assertions and strongly held feelings masquerading as fact. Those seem to me too commonplace to need a special name: humans are nothing if not motivated reasoners.

I think a better use for the coinage would be to single out utterances that are not motivated by any desire to express evidence-based belief, but that are clad in such utterances’ forms and signs. So something wouldn’t be “truthy” if it makes no claim at being based on objective evidence—it wouldn’t be truthy to recite your religion’s foundational dogma, or to say that someone is beautiful or to name your favourite meal. It also wouldn’t be truthy to provide facts or fact-based arguments. Truthiness, by my definition, uses the style, conventions and props of fact-based discourse—citations, experts, statistics—but lacks the substance.

In the past decade several people, I think independently, have suggested using the word “scienciness” by explicit analogy with truthiness. One definition describes it as the “illusion of scientific credibility and validity”, conveyed through “esoteric language and complex statistical representations…a rhetorical device to attribute the authority of science to methods and ideas possess little or no underpinning evidence or theoretical base”.

I have continued to reflect on the EPATH conference in Killarney last month. Last week I quoted Eliza Mondegreen (the pseudonym of a graduate student in Quebec), who attended both EPATH and the rival Genspect conference a mile away at the same time, but she’s written more since (here and here). She doesn’t use the word scienciness, but much of what she is talking about could be described as such.

“At Genspect, there were too many questions and so everything ran over time,” Eliza writes. “But down the road at EPATH, almost no one had asked any questions at all.” She was very struck by the fact that EPATH closed with the 1980s power ballad Don’t stop believin’: “Believin’ is the glue that holds everything together: the fantastical claims, the impossible promises transition makes, that data that suggests the wrong things to those of wavering faith.”

These are big giveaways that whatever was going on at EPATH, it wasn’t science. When science is being done, there are lots of questions, and the point of the scientific method is counter humans’ innate tendency to believe things that suit us, or to which we have prior commitments. But if you look at EPATH’s “scientific programme”, it certainly looks like science. It’s full of case-control and longitudinal studies, clinical outcomes, surgical advances, new techniques and instruments, hormone levels, sex ratios, biotin assays… “Scientific” is even right there in the name.

Eliza writes perceptively about the void she noticed at the heart of the EPATH programme, which combined lofty ideology and Frankenstein surgery but omitted any consideration of whether the ideology is well-founded or the procedures ethical. On the one side are paeans to the sacredness of the trans experience and waffle about online transgender singing groups and sex/gender tensions in cis (non-trans) individuals; on the other are dozens of papers about the myriad difficulties of chopping up genitals and restitching them in different configurations.

But the more I’ve thought about it, the more I’ve noticed something else: the whole thing isn’t just empty at its core, it’s superficial, even fake. I don’t mean that the findings of all these studies being presented have been falsified; I’m not alleging fraud. I mean, rather, that this isn’t really research at all. It’s not being done to find answers, or to shape professionals’ worldview or guide their day-to-day action. It’s performative.

A lot of the sessions were about experimental surgical procedures—ways to give men whose penises were stunted in adolescence by puberty-blockers a fake vagina by using colonic lining to compensate for the lack of penile tissue, or to give women who have taken testosterone a fake penis that can achieve an erection with the aid of a pump. These procedures have very high complication and failure rates. And even when things go as well as possible, no surgery on genitals can possibly produce functional organs of the opposite sex, or anything close.

But you don’t get any sense that delegates at EPATH thought such considerations should have any bearing on whether such operations should be done in the first place. The whole endeavour starts from the position that of course you would seek to reshape people’s primary and secondary sexual characteristics, if that is what those people want. I wonder is there any failure rate they would regard as excessive? Any procedure they would think too risky? They take it as given that doling out hormones and chopping up genitals progresses social justice, as long as it’s what the customers want. The sole eligibility criterion is consent. I genuinely think they might still go ahead if the patient was willing, even if the failure rate was 100%.

And so what are these studies and academic papers and conference sessions actually for? I suppose they allow you to choose between slightly different surgical techniques for procedures, even if you’re not going to ask the bigger questions about whether to do such procedures in the first place. If you have a prior commitment to doing “vagina-sparing metoidioplasty” for any woman who wants one (to take just one session title), then you probably want to do the neatest, safest job possible. But why would you have such a prior commitment? Nobody asks. Instead they keep believin’.

I was casting around for other examples of “scienciness” in the field of gender medicine and therapy, and they weren’t hard to find. I’ll just discuss one here: the extraordinary policy statement in 2018 from the American Association of Pediatrics entitled “Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents”.

All those citations and footnotes (94 of them); all the acronyms and definitions; the authoritative, abstract, impersonal language; the long list of “committees” and “liaisons” provided at the end, with the unstated implication that all these much-lettered people, with their MDs and PhDs, have thrown the entire weight of their learning and expertise behind it... It really looks like science! But if you go the bother of looking up the references, you quickly realise it’s not.

This statement, published by the largest and most prestigious professional association of paediatricians in the world, was devastatingly debunked by sexologist James Cantor shortly after publication, but has never been withdrawn or even edited. The sorts of errors Cantor found are not a matter of professional disagreement; all it takes to agree with his assessment is to actually read some links.

“As I read the works on which they based their policy however, I was pretty surprised…rather alarmed, actually,” he writes. “These documents simply did not say what AAP claimed they did.” One study was cited as proof that so-called conversion therapy for gender identity in children does not work and causes harm, but the paper actually concerned adults only, and sexual orientation not gender identity. Meanwhile all the studies demonstrating that gender dysphoria in children usually resolves were omitted without mention.

The most striking thing is, of course, that the AAP’s position paper is a complete distortion of the facts. But I think it’s also noteworthy that this distortion is dressed up as proper science. It’s not mere activist hyperbole about trans joy and TERFs allegedly inciting mass murder, or even the sort of opinion masquerading as news that has become far too common, not just in gutter outlets like Pink News but even at the BBC.

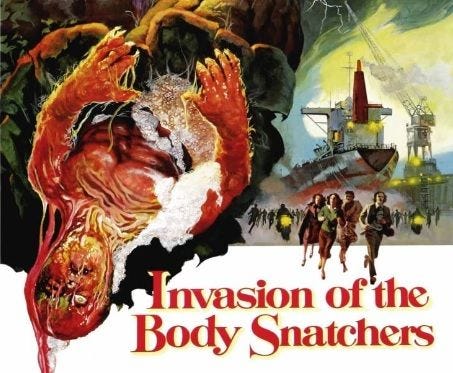

It’s a compliment to science, I suppose. But you cannot appropriate the form of a respected genre over and over again without destroying the reason for committing that appropriation, namely the trust that people place in that genre. The more this sort of thing happens, the less likely people will be to believe things that are presented as “science” or to trust anything scientists say. The entire scientific endeavour risks being destroyed by body snatchers who inhabit the form of science, but lack its animating spirit.