Being clear-eyed about protecting children

In this I pick up from the last-but-one edition, and consider what can be done to stop paedophiles offending.

This issue continues on from issue 41, in which I discussed the evidence regarding why some people, mostly men, abuse children, and why researchers distinguish this group from people who are solely or almost solely sexually aroused by prepubescent children. As I said then, the starting-point for protecting children from sexual abuse is to treat this crime as primarily one of opportunity, and to reduce the opportunities. But that may not be enough to deter those whose sexual desires are solely focused on children, and who must therefore maintain sexual abstinence—whether voluntarily or otherwise.

The idea of voluntary abstinence runs very much counter to the spirit of our age, which elevates sexuality above other personal characteristics and regards the suppression of sexual desire as automatically harmful. I think this is in part a pretty understandable reaction to the long suppression of homosexuality. Sexual orientation is a fundamental aspect of people’s personalities, and sexual love and relationships are among the great joys and sustaining experiences of adulthood. That gay people were denied these for so long is a tragedy and crime.

But the trend to liberate sexuality has gone far beyond the question of whether you want to sleep with people of the opposite sex, the same sex or both. It now encompasses the notion that everyone’s sexuality consists of a detailed list of preferences, usually framed as kinks. These range from the banal (praise, competence, rolled sleeves… I gleaned these from tags on fanfics!) to the esoteric (diaper-wearing, sissification, breath play [choking]…).

Behind this framing are two unstated assumptions: that kinks are something that come pre-installed, and are simply waiting to be uncovered; and that knowing and acting on your kinks is inherently good—who wants to be repressed or live in ignorance of their “true self”? Whether it might be better to live in blissful ignorance of the fact that, were you to try defecating in outsize nappies you might like it enough to want to do it all the time, never seems to arise.

I don’t think that people who subscribe to these unstated assumptions necessarily think their thoughts all the way through to the end. That is, I don’t think they would go so far as to believe that offending paedophiles have also found their true selves. But I do think such people are poorly placed to push back against paedophiles and paedophile apologists who argue precisely that.

Child-abuse scandals within the Catholic Church have also fed scepticism about the feasibility of sexual abstinence. I don’t think there’s any reason to think, however, that all or even most priests broke their vow of chastity, let alone abused children. It can’t be easy, but there certainly were and still are priests sustained by their genuine commitment to their God through temptation and loneliness.

Something more timeless also supports the thinking of paedophiles who offend: a false belief that men are prone to known as the “sexual over-perception bias”. This is the male tendency to interpret signals from people they think sexually attractive as come-ons: to see a colleague’s professional friendliness as a sign of sexual interest, or a date’s artificial smiles as keenness to move to the bedroom. Women, by contrast, experience a “sexual under-perception bias”—we think a man who asks us for dinner may be expressing mere friendliness, and that a date who offers to walk us home may be just being polite.

If you believe evolution shapes behaviour (spoiler, it does), both these biases make sense. The general pattern in sexually reproducing species is that “males display; females choose”. In mammals, that means males are opportunistic and females are picky, since the potential costs and consequences of mating for the two sexes are so very different. I expect I’ll have more to say in future issues about evolutionary psychology, but for now let’s just say that if you’re the type of animal who produces tens of millions of gametes in every short, easy-to-achieve orgasm, and need do nothing more to have the chance of sending your genes in the next generation, then acting as if any potential partner is interested makes sense. If you’re the type who produces at most a couple of hundred large gametes in a lifetime, which if fertilised will occupy your body and reproductive capacity for a significant part of your fertile life, it’s better to subject potential partners to much more detailed scrutiny.

And so paedophiles are pre-set, as men tend to be, to think and act as if the people they find attractive reciprocate that regard. This is amplified in situations where their object’s opinions aren’t considered important, as is often the case for women as viewed by men, and for children as viewed by adults. It’s hard to tell whether someone like Harvey Weinstein truly thought his power and influence made him irresistible to women, or whether he was aware of how repulsive he was being. He either didn’t know or didn’t care what his female targets thought and felt; the end result was the same.

In the case of paedophiles, the sexual over-perception bias is exacerbated by children’s natural playfulness and tendency to be physically affectionate, which a paedophile can easily see as a come-on. Add in the general tendency of humans to believe what they want to believe, and you have a dangerous cocktail. I know there’s an ick factor but push through it for a second: it’s essential to understand that these men really see children as provocative and knowing.

Another common belief among paedophiles that supports offending is that they are doing kids a favour by initiating them into sexual pleasure. Obviously this is just as self-serving as believing that the kids are coming on to them—people are very good at motivated reasoning that supports what they wanted to do anyway; paedophiles are hardly alone in that tendency. But anyway, that’s how it looks to them. If you want to stop them, you have to understand that.

There have been attempts to teach paedophiles that the beliefs that sustain their offending are false, and those attempts have about the level of success you might expect. Namely, not much unless the paedophiles are highly motivated to stop offending. To them it seems as obvious that children are sexy as it does to me that Chris Hemsworth is (Thor in the Avengers films, for those not up to speed with pop-culture references), and also obvious that children know it and are playing up to it, maybe even trading on it. I suspect that the paedophiles who have gone all in and spend their lives advocating for an end to ages of consent, like Tom O’Carroll, one of the founders of the Paedophile Information Exchange, find it so obvious that they think the rest of us see it too, and are simply lying.

Another approach is to give paedophiles drugs that dampen desire. Some years ago, for an article, I interviewed several paedophiles who had served prison sentences. One, an elderly American who had been convicted a few decades earlier of offences against boys aged 10-11, had voluntarily entered an intensive treatment programme upon release after his second spell inside. As well as undergoing a fair bit of counselling in which his false beliefs were challenged, he had taken libido-suppressing drugs. He welcomed the offer, he said, and thought they had helped him a lot because, he told me: “I still felt the attraction, but not the desire.”

When something is as dangerous and horrible as paedophilic sex offending, it’s tempting to think that you can fix it with force majeure, in this case chemical castration for all paedophiles, whether they consent or not. But that quote in the previous paragraph shows the problem: the attraction is still there, even if desire is dampened and perhaps the man is now unable to get an erection. If he didn’t consent to taking libido-suppressing drugs, he will also be angry at what is being done to him—these drugs are the same ones as are given for some cancers (and to block puberty in gender medicine, as it happens), and the side effects are no joke. To put it bluntly, men don’t need to be able to get erections to sexually assault and hurt children (or indeed women): they have hands, mouths and objects—and they also have fists. To the extent that their offending is driven by anger, sadism or the joy of forcing others to do what they don’t want to do, the offences may even be worse.

Other punitive measures sometimes imposed in an attempt to stop paedophiles reoffending include strict probation conditions and restriction zones intended to keep them away from children are. Of course, known child-abusers must be kept away from places where children congregate, and their crimes must be findable on police searches. But in some American states exclusion zones are drawn so widely, and rules on notifying the public are so extreme, that someone with a conviction for child sex-abuse will find sustaining any sort of normal life, or any work, impossible.

You might respond that you don’t care, and indeed child-abusers are about the most unsympathetic group imaginable. But we don’t exclude anyone from all of society, not even murderers. Hardly anyone gets a whole-of-life tariff. What matters when trying to protect children is what works.

And when it comes to other situations where people struggle to stop doing something harmful—drinking, taking drugs or engaging in behaviours such as self-harm and binge-eating, for example—it’s well-established that relapse is more likely when life is going badly. Treatment programmes for addiction and obsessive behaviours teach sufferers the mnemonic HALT: avoid getting too hungry, angry, lonely or tired, because that’s when your will-power is weakest and you’re most likely to make bad choices.

Risk factors for all sorts of re-offending, moreover, include social isolation, poverty, depression, stress—and stigma, which makes people more miserable, depressed, anxious, unable to work, socially isolated and despairing. So a paedophile who wants to avoid offending will find it easier if he has a steady income, somewhere to live, social support and at least a modicum of self-respect. He needs not to feel that is life is hopeless and that he might as well re-offend because he has nothing to lose.

This is an extremely difficult public-policy problem. On the one hand, helping convicted child-abusers regain some self-respect and hope for the future is an important part of helping them maintain self-control. On the other, stigma can be rather effective in reducing unwanted behaviours. Smoking bans reduce smoking by making it not only more inconvenient but also more antisocial. In places where marijuana is illegal, far few people use it than alcohol, and when it is decriminalised consumption goes up. Not all of that is because marijuana becomes easier to get hold of; it is also because quite a lot of people don’t want to do something that is stigmatised by being illegal.

Well, whichever outweighs the other, we are about to find out. A process of normalisation is currently under way in some “queer” spaces, in which the sexual boundary between adults and children is being blurred. In such spaces transgressive talk, if not action, regarding children and sex is increasingly welcomed—and among such spaces are many university departments and the sorts of “human-rights” charities originally set up to support gay people.

Here are three examples (in none of these cases am I accusing anyone of child molestation).

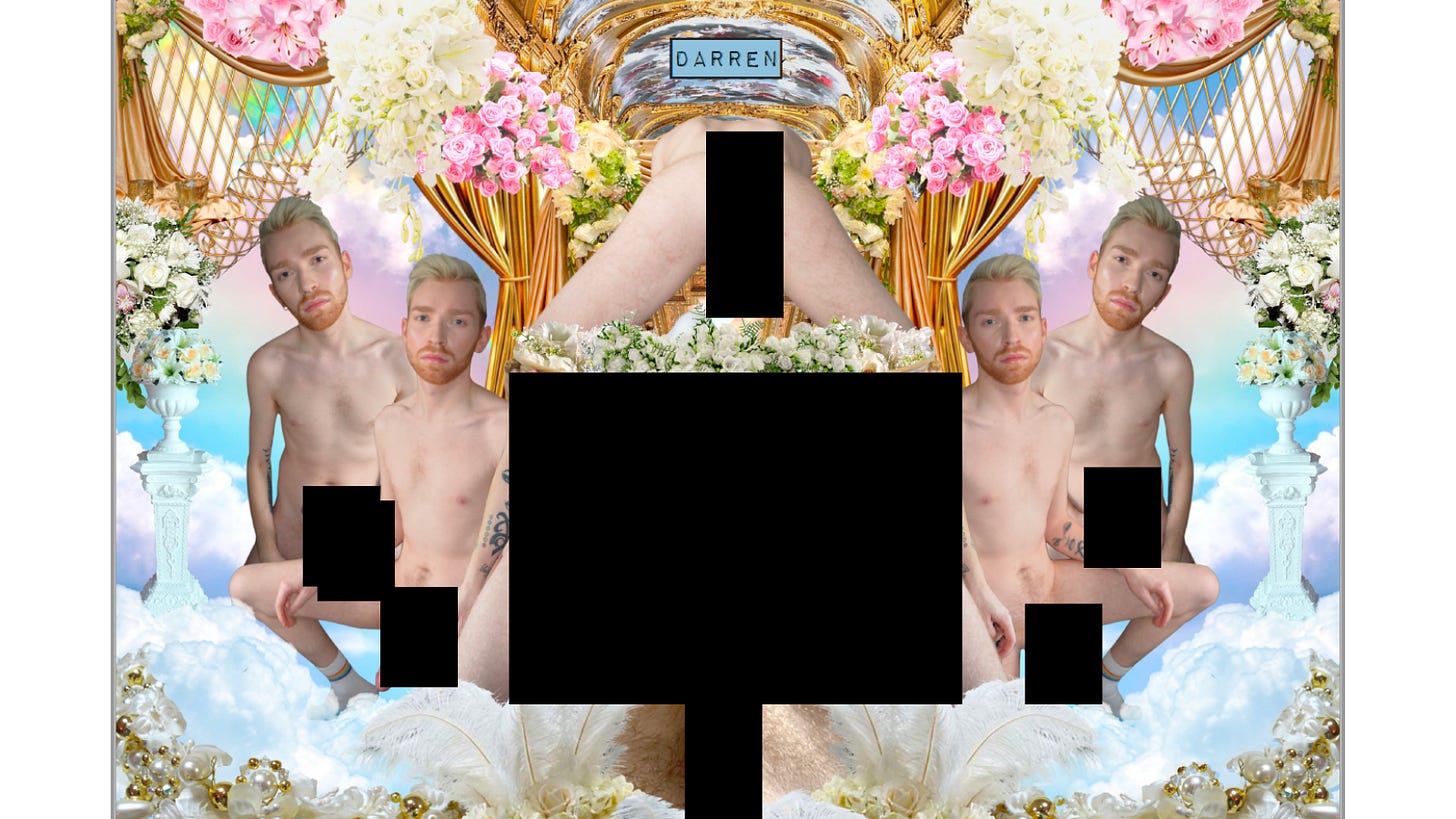

The first is Darren Mew, a young man who identifies as non-binary and who became digital officer for child-transition lobby group Mermaids in 2021. A few months ago it transpired that he had shared a picture of himself on Instagram dressed as a “sexy schoolgirl”. It was tagged “nonbinaryfinery” and captioned: “Sorry I can’t hear you. I’m just out here living my fantasy.” Mew also featured in a highly explicit naked collage for Haus, a digital magazine, which was shared on Twitter by the magazine’s account.

Whatever you think of pornography, it’s totally unacceptable for someone working for a charity that interacts directly with vulnerable children to appear in highly explicit pictures available online. All the more so, when that person is working in a role that involves overseeing digital interactions. The charity sacked him straight away, but it still beggars belief that he was ever regarded as suitable. (Maya Forstater’s Twitter account was suspended for quite some time for sharing the picture of Mew in Haus magazine, by the way, even though the original was shared by the magazine itself. I think that’s because the young people who work in social-media firms think that sharing explicit images for the purpose of showing that they are inappropriate is “kink-shaming”, one of the few remaining taboos.)

The second is Karl Andersson, a PhD student at Manchester University who researches how fans of subcultural comics in Japan experience desire and think about sexual identities. Andersson’s activities before starting at Manchester included creating Destroyer and Breaking Boy News, magazines dedicated to sexual pictures of teenage boys. While at Manchester, he published an “autoethnographic” article in a peer-reviewed journal that discussed his experiences of masturbating to nothing but Japanese shota—comics and cartoons featuring prepubescent boys in sexual situations—over a three-month period. (Autoethnography basically means writing about something you’re doing as if you’re both an exotic tribe and and anthropologist visiting that tribe.)

Andersson’s paper was pulled by the journal after a Tory MP tweeted critically about it. But neither the paper nor Andersson’s publication history raised red flags at Manchester’s Japanese Studies department, and quite amazingly, several academics popped up on social media to decry the “witch hunt” he had been subjected to. And before then, his work had been covered pretty sympathetically in Out magazine.

The third is Jacob Breslow of LSE, who works in the Gender Studies department at the London School of Economics. Breslow stepped down from the board of trustees of Mermaids after it was revealed that he had spoken at a conference organised by B4U-ACT, an American organisation that promotes understanding of “minor-attracted persons”. Promoting such understanding isn’t necessarily an issue—this article is seeking to do the same, though I don’t use that euphemism for paedophiles—but Breslow has gone beyond calling for understanding into paedophile apologism.

At the launch event for his book “Ambivalent Childhoods : Speculative Futures and the Psychic Life of the Child”, he said: “is it really that children or young people having sex is the problem? Or is it [the problem] the conditions under which that sex happens?” His PhD thesis hypothesised the “figure of the queer child…the child who displays interest in sex generally, in same-sex erotic attachments, or in cross-generational attachments”. In it, he also argued against “the child’s alleged asexuality” and proposed “allowing for the child’s pleasures, desires and perversities”. Again, this is not someone at all appropriate for a position of influence at a charity that works with vulnerable children.

A “love the sinner, hate the sin” approach seems to be about as good as we can get with paedophilia. But it’s hard when you’re up against edgy types, many of whom are probably not actually interested in sex with children, but like shocking the bourgeoisie—and patting themselves on the back for advancing social justice while doing it.