Nicola Sturgeon: my part in her downfall

(In case anyone thinks I’m taking more than my fair share of credit, the title is a joke, courtesy of Spike Milligan)

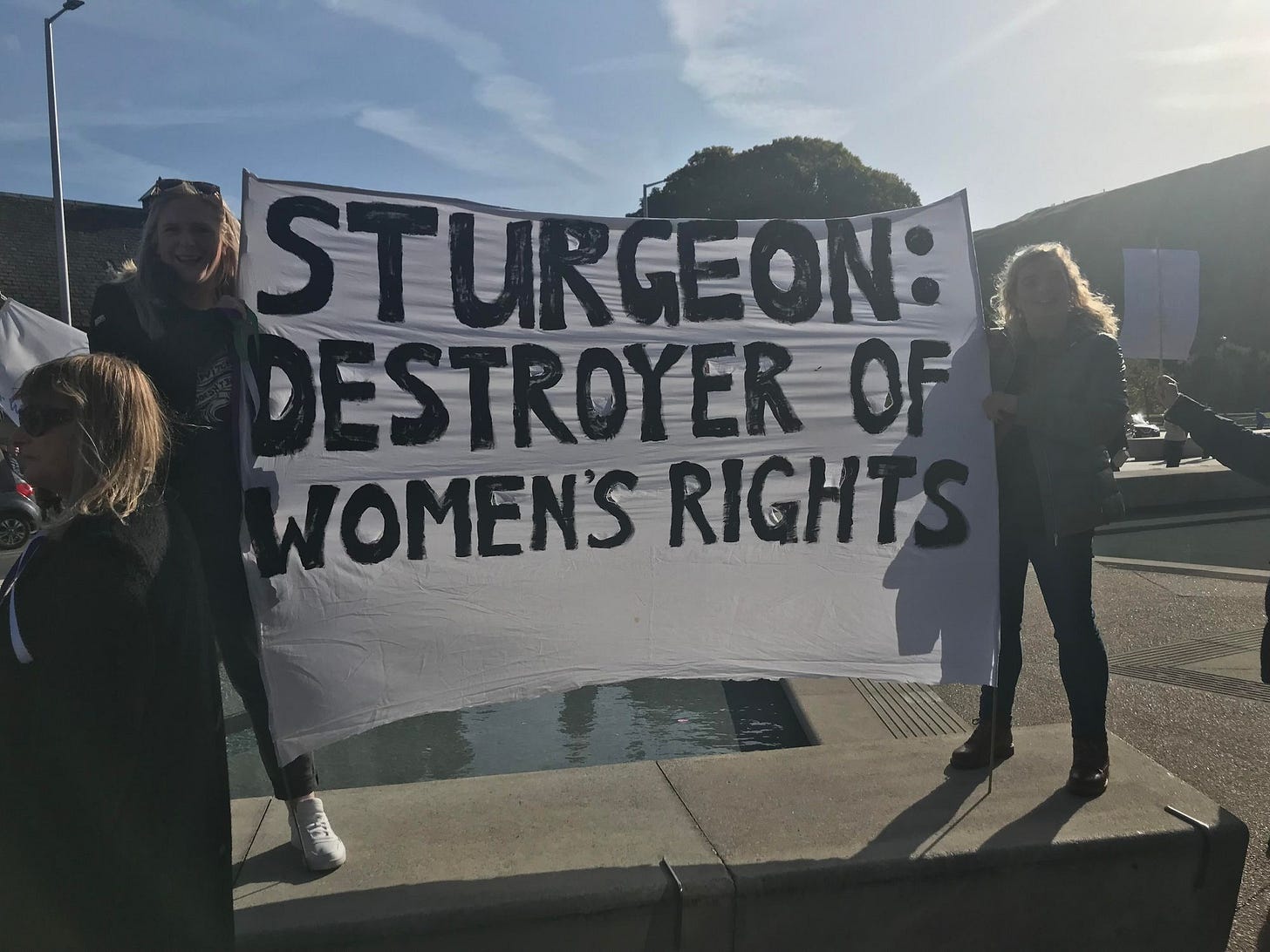

As I was deciding between several subjects for this week’s newsletter, the news broke that Nicola Sturgeon was stepping down as Scotland’s first minister. It was, of course, extremely welcome: on her watch Scotland has suffered a degree of capture by gender ideologues unmatched elsewhere in the UK. And so I thought I’d share some reflections on how this happened, and what it augurs for gender self-ID both in Scotland and elsewhere.

If you are not a subscriber to my weekly newsletter, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

The first thing to understand if you don’t know Scottish politics is that most Scots—more than 90%, according to this article in The Economist from March 2022, which I commissioned and edited shortly before I took leave of absence—are sure, or nearly so, which way they would vote in any future independence referendum. Most supporters of independence vote for Sturgeon’s Scottish National Party, with a small share going to the Greens, who have a formal arrangement supporting her. The unionist vote, by contrast, is split more evenly between the Conservatives and Labour.

That means the SNP is pretty much guaranteed always to form the government—at the moment it holds 64 seats of 129 in Holyrood, with the Greens accounting for another seven. The Conservatives and Labour have just 31 and 22 respectively. And as any economist will tell you, lack of competition to form the government means very poor government.

Not only is the SNP the permanent party of power; there is very little check on what that party can do. The Scottish parliament is unicameral—that is, it lacks a revising chamber like the House of Lords. Civil servants depend more on the SNP than they would if power rotated—officials know that the party can make or break their careers. What has made things worse is Sturgeon’s political style, which prioritises loyalty over honesty or wisdom. She keeps her counsel with a tight-knit circle of intimates, and anyone who challenges her is cast out.

The result of all this is that since 2014, when Sturgeon took over as leader of the SNP and Scottish first minister, her word has been law. And often bad law, unsurprisingly given the lack of meaningful challenge, competition or oversight.

In late 2021 I wrote about Scotland’s creeping authoritarianism for The Economist’s annual publication, The World Ahead, as the government was forcing through the latest in a series of ill-conceived and incompetently drafted measures that restricted speech and intruded in private life to a degree that would surely have been impossible if the country had any effective opposition. So bad were some that they were overturned on constitutional grounds or, like the last and worst at the time I was writing, the Hate Crime and Public Order Act, have been impossible to implement. That law created a new offence of “stirring up” hatred, criminalising utterances considered inflammatory or insulting even when they caused no actual harm and are not intended to incite a specific act.

Civil society, too, has been captured. In an incestuous, corporatist money-go-round, the government pays lobby groups to recommend policies it has already decided on, and then pays its pet charities to implement those policies. Scottish journalist Susan Dalgety revealed in a recent article for the Scotsman how this process of policy-laundering got self-ID onto the political agenda in Holyrood, and then into practice and then into law—nearly; Sturgeon’s departure surely means the Gender Recognition Reform Bill, already on hold after challenge in Westminster, will be hard to revive. (You can read Dalgety’s article on her Substack).

This is why the only challenge to gender self-ID law has come from nippy new grassroots groups: the established women’s charities know too well which side their bread is buttered on. For Women Scotland, which went to court to block the SNP’s law defining “woman” as anyone who says they’re a woman for the purposes of quotas on public boards, and policy house Murray Blackburn Mackenzie, which has consistently produced the best critiques of the Scottish government, were—in the words of a recent Times article about MBM—“the effective opposition to Nicola Sturgeon’s government”.

In the feverish scramble before Christmas, as Holyrood sat long hours to force through the Gender Recognition Reform Bill against all attempts to limit its harms by passing amendments, the years of work by this “effective opposition” finally started to bear fruit. Anywhere you ask people what they think about self-ID they’ll tell you they don’t like it; the trouble is that most don’t know it’s happening. But these women’s work meant that, increasingly, Scottish people did.

And then, after Christmas, along came Adam Graham/ Isla Bryson, whose gender dysphoria suddenly struck as he was awaiting trial. Here was a villain straight from central casting who would have been rejected by any self-respecting screenwriter as simply too on the nose: face tattoo; ACAB written across his knuckles; thick neck; dead-eyed stare—and now a conviction for two rapes. On conviction he was set to be incarcerated in Cornton Vale, Scotland’s sole women-only prison; the public outcry kiboshed that, and then cast self-ID in doubt.

Once a story is out, it’s out—as a riveting poll published by UnHerd on February 10th showed. Not only are the consequences of self-ID very unpopular across the UK once you ask a clear enough question; they are more so in Scotland, where the voting public knows most about them. On every one of the four questions the pollsters put to members of the public, the most “trans-sceptical” constituencies were in Scotland. And that awareness is only going to increase further. Every day now there is something else in the press on the horrors of self-ID. Wednesday’s story was that four out of five of the men incarcerated with women in Scotland on the basis of self-ID are murderers.

Part of the reason familiarity breeds scepticism is that, for the unfamiliar, the transactivist language is discombobulating. As Kathleen Stock points out in her UnHerd column commenting on the same polling results, many more people agree that “trans women are women” than think that “trans women” should be able to use women’s spaces. That suggests, she points out, that “when push comes to shove, most people do not believe that trans women are women. For the alternative doesn’t add up: large sections of the British public believe there is a kind of anomalously shaped, baritone-voiced woman out there who also, for some reason, shouldn’t be allowed in a female changing room or on the sports field with other women.” (Last-minute edit: Kathleen’s UnHerd article today on Sturgeon is scathing, and absolutely brilliant. Do read it.)

No doubt Sturgeon’s career was ended by several factors. During her eight years as first minister support for independence fell. Police are now investigating allegations of serious financial wrongdoing within the SNP. How much of a role self-ID played is a matter of conjecture. But I’m not the only person who thinks it played a central part. Becoming inextricably associated in the public imagination as the woman determined at all costs to enable male rapists and murderers to gain access to women’s prisons is hardly a winning political look.

If you would like to become a paid subscriber and receive full access to my weekly newsletter, you can sign up here.