The meaning of sex — and of news

The upcoming Westminster Hall debate on what sex should mean in the Equality Act, news cycles, Kathleen Stock — and memes.

A relatively short update this week, since it’s all hands on deck at Sex Matters as we prepare for a Westminster Hall debate on June 12th. Two petitions are being discussed during the same session: ours, calling on the government to make the definition of the protected characteristic of sex in the Equality Act clear; and a rival one calling on the government to leave it a muddle. It’s happening from 4.30pm, and will be broadcast live on Parliament TV and live-tweeted by @tribunaltweets.

If you are not a subscriber to my weekly newsletter, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

This week Sex Matters has published several blogposts about some aspect of the proposal: Why the aim isn’t to insert the word “biological” before sex in the Equality Act; Why sex and gender mean the same thing in (UK) law; why sex must mean sex throughout the Equality Act; what a gender-recognition certificate does (and does not) do; and how the public-sector equality duty was turned against women. And next Thursday we’ll be broadcasting a live webinar at 7.30-8.30pm UK time, with Naomi Cunningham, our chair, and Michael Foran, a law lecturer at Glasgow University who has written extensively and usefully on the Scottish Gender Recognition Reform Bill and much else related to sex, gender and the law.

In UK laws, there are only two possible meanings for “sex” (and indeed gender, which is simply a synonym for sex): either it carries its common-law meaning, namely male/female; or it means “sex as modified by a gender-recognition certificate (GRC)”. There’s no single meaning for “legal sex”, therefore, and it’s an expression I try not to use because it gives the impression that we all have a legal sex, which may or may not be the same as our actual one. In the UK, at least, that’s not really accurate. We all have certainly a sex, but about 6,000 people—those with GRCs—are treated for certain laws as if their sex were the opposite to what it actually is.

So what the word “sex” means varies from one law, and one legal purpose, to another. Specific provisions in the GRA mean that those 6,000 people, like the rest of us, are recognised as members of their own sex when it comes to parenthood, sex crimes and inheritance of estates and titles, but are treated as if they are members of the opposite sex when it comes to marriage and pensions.

Arguably, in the Equality Act sex means “as modified by a GRC” because the GRA says a GRC changes your sex for the purposes of all laws unless specified otherwise. That is what Lady Haldane concluded in a ruling in Scotland just before Christmas concerning a challenge brought by campaign group For Women Scotland to the use of the “as modified by a GRC” definition in a Scottish law intended to increase the representation of women on boards.

That ruling is being appealed, however. Those who think it was wrongly decided would argue that it unlawfully destroys a variety of human rights, including some that flow from the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, which was rolled into the Equality Act in 2010. In essence, the “modified by a GRC” interpretation would mean that women as a group are no longer recognised as a proper target for measures to tackle sex discrimination. It seems unlikely that Parliament really meant to destroy the very concept of sex discrimination in 2010.

Ambiguity about what sex means in the Equality Act suits transactivists, who shamelessly claim it means whatever suits them at any given moment. In 2018, when arguing for legal gender self-identification, they claimed that a GRC is a mere formality that makes people feel seen but confers no new rights. Stonewall, for example, said back then that a GRC made a difference only for birth certificates, marriage and pensions. (This page has since been removed from Stonewall’s website; here’s a screenshot.)

Around the same time, the Guardian commissioned six different viewpoints on the merits or otherwise of gender self-ID. Two of the authors were trans legal academics: Stephen Whittle and Alex Sharpe. Both argued that a GRC was basically just paperwork, and certainly did not have any wider impact on, for example, single-sex spaces. You can read their takes, and four others, here.

If that is the case, a GRC cannot possibly change a person’s sex category for the purposes of the Equality Act—and yet now Whittle says it does so for ALL purposes, and that anyone who claims otherwise wants to strip trans people of their rights. Stonewall, for its part, promoted the rival petition to Sex Matters’, which claims that clarifying that sex means sex “would remove a legal protection for trans people and encourage discrimination”.

But ambiguity certainly doesn’t suit service-users, who risk nasty surprises when they enter spaces they thought were single-sex only to discover someone of the opposite sex (in homage to automated checkouts, I call this “unexpected genitals in the disrobing area”). It doesn’t suit service-providers either, since they don’t know what to do to keep customers safe and happy—or indeed to avoid getting sued. The government’s dilatoriness in fixing this has been cowardly. It has pushed legal and reputational risk, and the miserable business of facing down deranged transactivists, down onto individuals and businesses.

The debate in Westminster Hall won’t be followed by a vote. If the government does decide to amend the Equality Act to put beyond doubt which of the two meanings “sex” holds in that act, it will do so by means of a statutory instrument (this is a way to amend legislation without having to pass a new law). The point of the debate is to give the government a sense of the arguments and level of support for doing this—and to give it courage.

Whatever the government does at this point, it is sure to face serious opposition: if it acts, from transactivists; if chickens out, from gender-critical feminists. But the right place to fix this mess is not the courts. It’s not the job of busy, unfunded women to chase legal actions up from one court to the next, putting their lives on hold, attracting serious vilification and reliant on crowdfunding all the way; it’s for lawmakers. They caused this problem with poor drafting and wishful thinking; it’s well past time that they sorted it out.

The other big gender-critical news this week is, of course, the ongoing hoo-ha about free speech in universities. It has finally found its figurehead: Kathleen Stock. News is funny that way; stories swirl amorphously until they coalesce around a “narrative”, at which point everyone suddenly knows what they are about—and whom.

In part the sudden newsworthiness of free-speech concerns is about pitch-rolling: worries that universities have become censorious places have been growing for years. And in part it’s timing. Channel 4 had been working on a documentary entitled “Gender Wars” since last year, and by coincidence it aired on the same day as Kathleen gave a long-trailed and much-protested-against talk at the Oxford Union. Actually, I don’t think coincidence is really the right word. Some journalists have an excellent nose for news, and seem to be able to engineer these sorts of coincidences much more often than chance could possibly explain. So hats off to the C4 documentary-makers, who landed a great story at the perfect moment, while their counterparts at the BBC and in ITV and Sky are still pretending there’s nothing to see here.

It’s also because Kathleen is so personable, eloquent and transparently decent. I know from friends who were in the documentary (and couldn’t tell me beforehand because they had signed an NDA) that the original intention had been to feature a more ensemble cast. But as soon as they interviewed Kathleen it became clear they had found their main protagonist.

The transactivists who were interviewed have, predictably, complained. Some have said they wouldn’t have taken part if they had known the documentary would be so sympathetic (for which read “at all sympathetic”) to their opponents (here’s Whittle again). Honestly, that is the risk you take when you agree to be filmed—the gender-critical women I know certainly worried that they had been stitched up right until they saw the final cut. And even having read that blog by Whittle I’m not sure what actual misrepresentations are being complained about, as opposed to just not liking the overall balance.

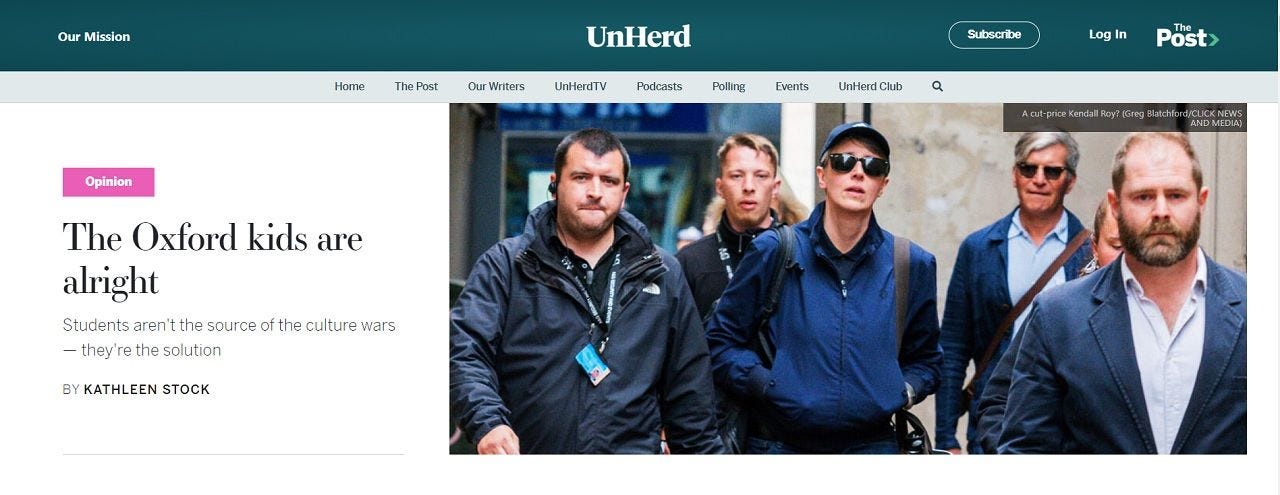

Another thing that gave this story legs is that it produced not one but two iconic photographs. The first was of Kathleen, accompanied by her security detail, walking to the Oxford Union talk and looking effortlessly, enviably cool and unruffled—in her UnHerd column she says she didn’t feel calm, but she certainly looks it. The picture is both striking and surreal: she’s a philosophy professor arriving to give a talk at one of the world’s great universities on what ten years ago would have seemed too trivial even to need stating, namely the existence and salience of the two human sexes—and it looks like a publicity shot for a new police-procedural show.

If possible, I like the second picture even better. It’s of Riz Posnett, a they/them student and environmental protestor who glued her hand to the floor during the talk and managed to halt it for half an hour. Her affectedly pious expression, and Kathleen’s “toddlers gonna toddler” face in the background, would already make for an excellent shot. But the way Riz’s head look like it’s been cut off and placed on the desk makes it really special, and memeworthy.

If you would like to become a paid subscriber and receive full access to my weekly newsletter, you can sign up here.