What do Generation Revolution really think?

Now that the dust is starting to settle on the FWS Supreme Court judgment, I’m thinking more about public opinion - especially among the young.

The fallout from the Supreme Court judgment shows no signs of abating any time soon, but the immediate rush has calmed down somewhat. And so in the past couple of weeks I’ve had a bit more headspace, and have started to think again about one of my major preoccupations: what do young people really think about gender-identity ideology, and to the extent that they truly believe in it, how can that be changed? Because if the rising generations think that single-sex spaces are bigotry and that men make the best women, then it doesn’t matter what the law says now: in the long term generational change means we will lose.

If you are not a subscriber to my newsletter, Joyce Activated, you might like to sign up for free updates. I hope that in the future you might consider subscribing.

Opinion polls find four big factors that affect people’s opinions on the tenets of trans ideology: age, sex, politics and education. Being young, female, left-leaning or a university graduate all make someone more likely to agree that “trans women are women”, plus the related beliefs (such as “puberty blockers are life-saving”). These are somewhat confounded – more girls than boys go to university, girls are more left-leaning than boys and young people are more likely to be left wing and more likely to be university graduates. But in any case, the age gradient is very strong. Hardly any over-65s believe TWAW; a large share of under-25s do.

If younger age groups maintain their current position as they age, and if the age gradient continues on the same trajectory, then it doesn’t matter what the Supreme Court said. The UK will end up with legal gender self-ID, not by stealth as it’s been introduced everywhere that already has it, but by popular demand.

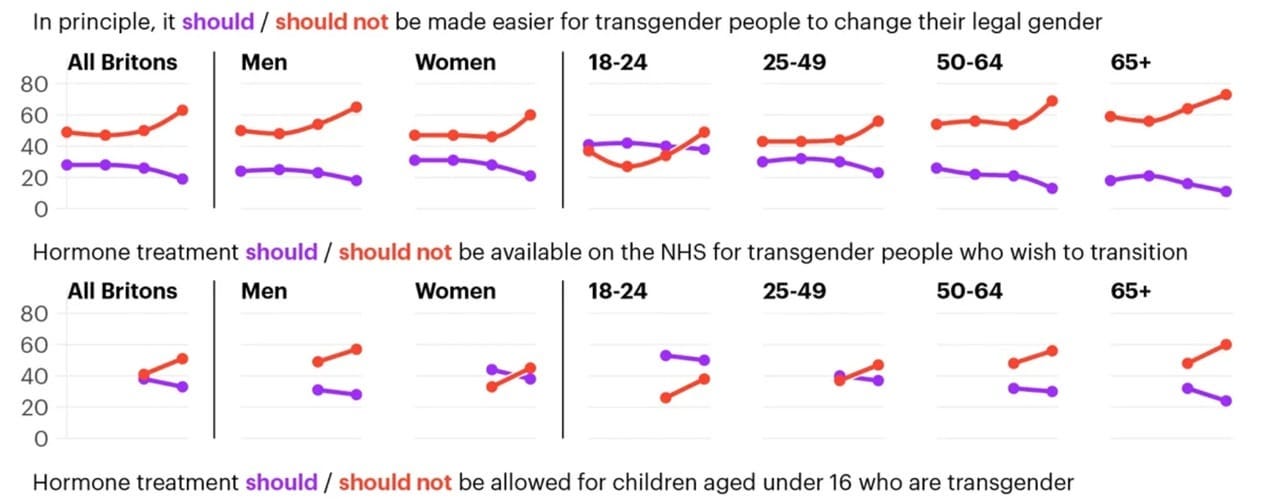

The most detailed breakdown of attitudes by age that I have found is here, from British pollster YouGov (the picture above is a screenshot of the results for two of the questions). It both illustrates the immensity of the age effect, and gives some cause for hope.

I strongly urge you to click through and look at all the charts; literally every line is fascinating. I have three main takeaways. The first is that young people are enormously more “trans positive” than older people – on nearly every question, by at least 20 percentage points, and often much more. The second is that their opinions have shifted in the past two years by at least as much as other age groups, and in every case it’s been away from the trans-positive position. The third is that this change isn’t merely a decrease in support, or an increase in negativity – it’s both.

The charts use purple lines for what I would characterise as the wrong answer to each question, and red lines for the right ones. Some questions have been asked four times – every two years, starting from 2018; others just twice, in 2022 and 2024. Click through, and let your eye scan across the images, keeping in mind that “purple is bad, red good”, and you will see an immensely encouraging pattern: on literally every question, and in literally every demographic, things have improved over this relatively short time scale.

Obviously, some people won’t stay in the same age group right through the period surveyed. Most people in the 18-24 age group in 2018 will be 25 or over in 2024. But these changes can’t be explained by people ageing out of one group and into the next, because the movement in opinion is in the wrong direction. People are ageing out of more trans-positive age ranges into less trans-positive ones at the same time as every group is becoming less trans positive. This means the effects at the individual level must be even stronger than they appear by tracking cohorts.

If you’re not following, imagine that nobody at all ever changed their mind on this topic, but the age-cohort differences were precisely as they appear in these charts in 2018 (or 2022 for the questions that have been asked only twice). Then every year you would see some people age out of more trans-positive age groups into less trans-positive ones, thereby making their new age range more trans positive, not less. That we see the opposite of this means we can be sure individuals are changing their minds, and by more than the within-age-cohort changes would suggest if there wasn’t any churn.

I also find it encouraging that both the red and purple lines move in nearly every one of these charts (almost the only exception is when it comes to hormone treatments for under-16s, which almost nobody over 25 ever thought should be allowed – there just wasn’t much room for that purple line to fall any further). This means young people aren’t just losing interest in this topic, perhaps seeing it as boring or passé. Their opinions are actively hardening against trans-positive positions.

Literally the only line I find disturbing in the whole set is in response to a question about whether increased recognition and rights for transgender people poses a genuine risk to women’s rights, where, among 18- to 24-year-olds, both the share agreeing and the share disagreeing have risen.

So what to make of all this? The first thing to say is, it’s a highly unusual set of results. Public opinion on this sort of thing doesn’t usually change so much, or so fast. It’s not like people’s opinions of the prime minister, which are based on trivialities and flit up and down. This is a significant and live policy issue – it’s something like Brexit. And as someone deeply involved in the pro-Brexit campaign recently told me, almost no one’s opinions changed during the very heated runup to that vote. All that happened to confound the pollsters and get his side over the line was that habitual non-voters turned out and voted Leave.

People’s opinions on social and political issues don’t usually change much after their “formative period” – that is, their youth (there’s a reason it’s called your formative period). At first this finding surprised me. I had thought it was well-established that people got more right-wing as they got older, but apparently it’s nothing like that simple. Different studies come to somewhat different conclusions, but most find that ageing has a minimal effect on political position.

That means culture wars are usually “long wars”, won by generational change rather than by changing individuals’ positions. But then again, those YouGov charts suggest trans issues might be different. Why?

As I’ve mentioned in several public interviews, I’ve watched focus groups in which people discussed various trans-related issues. And one of the many things that came out was how extraordinarily shallow people’s opinions are on this subject. Most people started by making broadly supportive statements – everyone knows themselves best, people should be free to live however they feel most comfortable, it must be awful to be born in the wrong body, trans people are an oppressed minority – and then at the slightest challenge (“What about single-sex spaces?” or “what about children?” or “what about sports?”) they would immediately and unhesitatingly flip, saying “oh, I didn’t think of that,” or “oh, not in sports” or “of course kids are too young to do anything irreversible.”

The strong impression I got was that nearly everyone starts out unthinkingly saying “live and let live” (several used that exact expression) and totally misunderstanding the enormity of the trans lobby’s demands on other people. They were sure that there was a special sort of person who was “born in the wrong body” and that doctors were able to tell which people were “true trans” and chancers. They weren’t at all sure what was involved in transition, but clearly thought that trans people went through enormous physical changes that made them pretty much indistinguishable from the opposite sex, or at least proved they were very serious about their transition and it would be mean to deny them after all that. They were aware that this was a heated topic and one where it was unwise to step out of line. When asked a question that conflicted with their desire to live and let live, they quickly retreated to “it’s complicated”. Overall, support for trans demands could be summarised as “a mile wide and an inch deep”.

But young people are steeped in it. Many have been taught rubbish in school about sex being a spectrum or indefinable, and almost all will have friends or classmates who identify as trans or non-binary. Those that go to university will find it near-impossible to avoid further attempts to indoctrinate them. This has been going on so long now that I think it may now be self-sustaining, at least for girls.

Until relatively recently the transmission of knowledge and attitudes through the generations was largely through families, workplaces and a few large institutions such as churches. Now it’s largely through formal education, social media and the entertainment industry, broadly defined (computer games, film, television, comics, to some extent books and – a controversial entry in a list of entertainment-industry organisations! – certain charities and NGOs).

That concentrates the shaping of the next generation in the hands of a much smaller number of older people – largely university lecturers, school-teachers and people who are influential in the media, such as influencers, famous actors and singers, commissioning editors and scriptwriters. But also – and this is historically unprecedented – in the hands of their own age group, in situations unmediated and entirely unobserved by their elders, namely on social-media sites such as Reddit, TikTok and until recently Tumblr, and on Discord servers and in WhatsApp and Signal groups and in-game chats.

Self-organising mixed-age institutions like churches and sports clubs play an awful lot smaller a role than they used to. Parents and employers are practically sidelined. You can of course try to instil your values in your children at home, and that’s important – but unless you are hyper-liberal, all the other influences on your children are probably working against you. Schools now encourage children to think of their parents as backward, bigoted fools who need re-educating by their enlightened offspring.

Employers don’t know what to do with new hires who expect to bring their whole selves to work, seem to hold inexplicable values and have clearly not been socialised in basic employability skills. They certainly don’t seem to feel they have either the right or the ability to reject the new, alien and objectionable workplace norms that many young people demand.

Putting this all together, I really don’t know what to think about stopping the transmission of gender-identity ideology to new cohorts. On the one hand, clearly significant numbers of young people are rejecting it despite all these headwinds. On the other, young people are still, on balance, very trans-positive, and the various routes whereby they are influenced seem very hard to shift.

In particular, the system whereby older women indoctrinate younger women and girls seems close to self-sustaining. Female academics in subjects like sociology, gender studies and the like have already bought into trans, and teach mostly young women. Those young women become lecturers in these female-heavy subjects, as well as school-teachers, social workers and HR professionals. They go to work in charities, publishing, regulators, the civil service and the healthcare professions. They both replace the women who first indoctrinated them and also make up the “lanyard class” that hectors everyone into good behaviour, defined in progressive terms.

I think this helps explain another huge generational story: the divergence between boys and girls, and young men and women. Have a look at the charts in this Financial Times article from last year, which document a quite extraordinary political divergence between the sexes in recent years. Young men and young women are rapidly growing apart, with boys now far more right wing than girls. Which sex has moved the most varies from country to country among the four pictured. But the gap is now so wide in all of them that you really wonder what your average young heterosexual couple finds to talk about.

In trying to think about how young people’s opinions might change in the coming years, one big question is how young people will react to changing laws. Polling by YouGov commissioned by Sex Matters shortly after the Supreme Court ruling found very high awareness and approval of the outcome across nearly all age groups – but not among the youngest, who were both more likely to say they knew about the judgment and more likely to say it was the wrong result and/or harmful. In the US, young people who have been told for years that puberty blockers and gender-affirming care are “life-saving” must be distraught in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Skrmetti, which means about half of the states are now going to ban both.

I can’t even begin to hypothesise about how these mismatches between important and necessary legal measures, on the one hand, and many young people’s ill-founded but strongly held beliefs, on the other, will play out.

And what of changing fashion? Might the sheer ubiquity of trans ideology in educational institutions make it seem lame (if your teachers are pushing it, it can’t possibly be edgy)? If 18- to 24-year-olds are very keen on it, can it possibly still seem super-cool to under-18s? Anecdotally and by looking at the young people who turn out on trans marches, it really doesn’t seem that those identifying as trans or non-binary are the popular, conventionally attractive kids – many look like sweet but somewhat quirky types and some look quite unwell. Might that make it less aspirational?

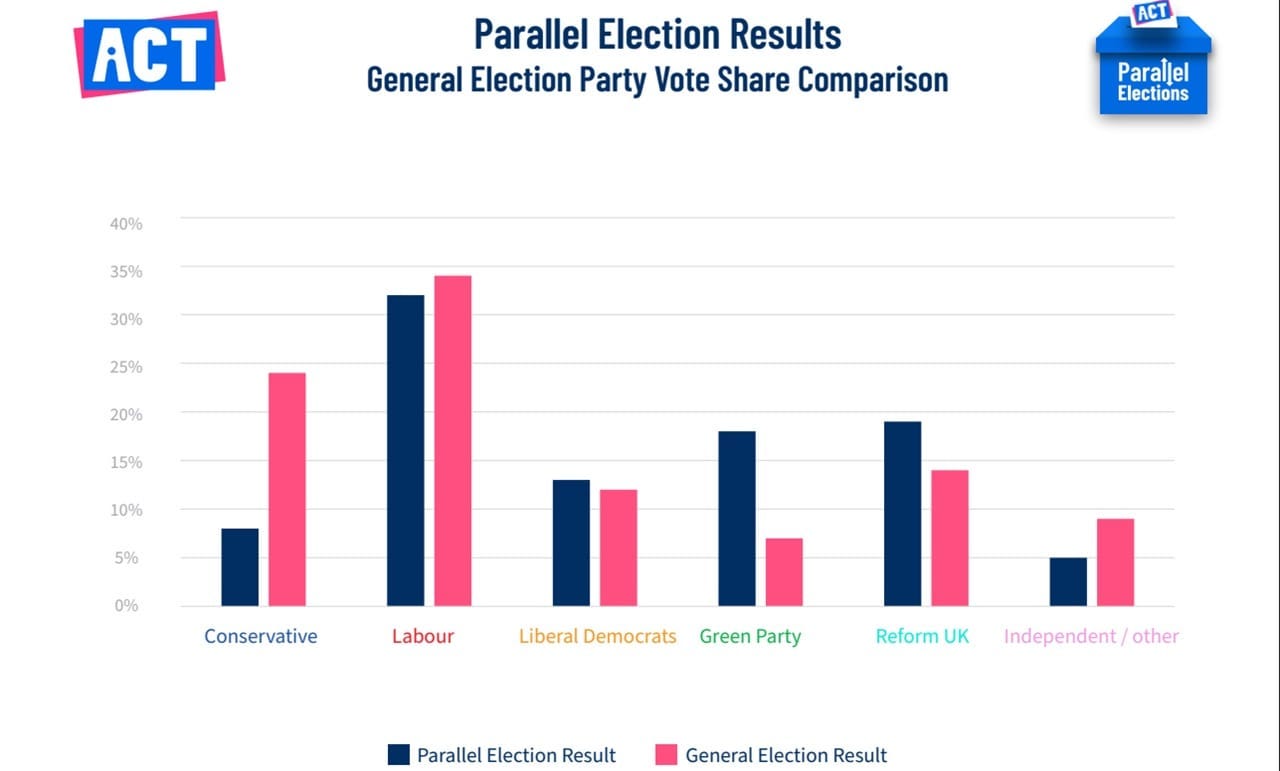

And what about the way politics more widely is changing? We live in turbulent political times, with some established parties like the Conservatives polling at historic lows, and political upstarts winning elections. And although young people tend to be more left wing than older people (in the UK at least, by an enormous amount), they are also more polarised, and the right-leaning ones are very right-leaning.

Several organisations in the UK support schools to run mock elections before general elections as an exercise in democratic education. Below is a screenshot of the results of one of the biggest, with a useful side-by-side comparison with the actual election result. In brief, the share of under-18s “voting” Labour was about the same as among actual voters, the share voting Green (in effect, far left) was far higher, the share voting Conservative was far lower and the share voting Reform (hard right) was higher.

When it comes to the way young people’s opinions may change, there are so many moving parts it’s hard to make predictions, and very hard to know which levers it might be most effective to pull. But there is one obvious, large, centralised effect on children and young people that has been working in the wrong direction and that might, at least in principle, be possible to influence for the better. That’s the education system. I’ll look at that in more detail in the next issue.

If you are signed up for free updates or were forwarded this, and would like to subscribe to my newsletter, Joyce Activated, click below.